Torres del Paine is one of the most visited national parks in Chile, located in the Magallanes region, in the southernmost part of the country. Within the park’s vast area are parts of glaciers that extend from the South Patagonian Icefield on the west and expansive, arid plains to the east.

The weather here is unpredictable; intense rain can suddenly give way to winds averaging 80 kilometers per hour, with gusts reaching up to 130 kilometers per hour. Yet, within a few hours, the sun might shine, bringing a sense of calm. It’s often said that in Patagonia you can experience all four seasons in a single day.

I’ve been working in the area for 16 years, and this place has captivated me from the very beginning. I’ve had a love for animals since I was very young and am a veterinarian by profession. However, the opportunity to interact with and, in a way, understand wild animals in their natural habitat has always been my greatest curiosity.

Living in Torres del Paine and wandering through the pampas, I began to familiarize myself with the pumas. Studying their behavior, seeking them out, walking alongside them, and tracking the lives of different individuals over the years has been truly mesmerizing.

Over time, I’ve had the chance to closely follow the lives of specific pumas, establishing a connection with them. Capturing our encounters through my lens has fulfilled me both personally and as a photographer.

For me, conservation is the goal, and I’ve found photography to be the medium through which I can convey this message.

Getting Close to a Puma

The puma (puma concolor) is a relatively elusive creature, solitary in nature, with predominantly nocturnal and crepuscular habits. Pumas are most active during times when temperatures are cooler with minimal fluctuations. This is why the search for them begins very early in the morning, approaching their territories in off-road vehicles. Once there, the trek and search with binoculars commence. It’s a hunt that requires immense patience, and knowledge of the terrain and its colors and of the shapes of both the landscape and the puma. Given that the puma’s coat closely matches its surroundings, it blends in seamlessly.

Once one is familiar with all these details, finding the puma isn’t the most challenging part. The real complexity lies in the subsequent strategy: approaching and positioning oneself at a safe distance from the animal. The goal is to observe and appreciate the puma without in any way altering its behavior, causing stress, or prompting it to leave due to our presence.

Depending on the individual, the approach can take just a few minutes, or it can be quite lengthy. It also depends on what the puma is doing at that moment — whether it’s eating; if it’s a female with a cub, a male, or a more skittish puma; and the type of terrain it’s on, among other factors. And these are things only those of us on the ground, familiar with the individual pumas, truly understand.

Just like humans, every puma has its own unique temperament, so it may act differently from other animals. It’s possible to interpret these moods, and from there make the decisions necessary to capture a visually striking image. Above all, the well-being of the individual puma is paramount.

For me, photographing pumas was at first more about documenting the individual pumas rather than focusing on composition. The fleeting encounters didn’t give me much time to think; I could only manage to quickly raise the camera and snap a photo without shaking, all while handling the excitement and adrenaline of the moment.

Photography Progression

In the beginning, my puma photographs were primarily portraits, well-exposed shots focusing mainly on details that would allow me to identify individual pumas. I also have a keen interest in capturing unique interactions, and in those early years my focus was predominantly on the subject itself. I aimed for sharpness, blurred backgrounds, and the spotlight solely on the puma. To achieve this while maintaining a safe distance (about 50 meters), the use of telephoto lenses was essential. Back then, I had a fixed 500mm lens, which meant I was carrying a significant amount of weight. Additionally, the zoom lenses available at that time didn’t offer the optical quality that we see in today’s models.

I recall an instance in 2010 when we spotted a puma, roughly 2 years old, that was quite a distance away. A ravine formed a significant physical barrier between us and the animal, and the puma seemed quite relaxed after a meal (we could see bloodstains on its muzzle and fur). It was basking in the sun, warming itself before likely seeking a sheltered spot to rest. I had the chance to use a 600mm lens with a tripod and, with a wide-open aperture, I captured an image.

However, I wasn’t entirely pleased with the shot, primarily because, in the distance, parts of the glaciers from the South Patagonian Icefield were visible. To me, the image felt lacking, mainly because the background wasn’t uniform. I shared the photo on a platform where it received critical acclaim. The feedback notably highlighted the significance of the white backdrop, suggesting that incorporating more of the landscape would have added context and enhanced the image’s appeal.

At that time, I didn’t heed this constructive criticism and continued with my usual style of photography, focusing on portraits with blurred backgrounds. This particular photo was chosen by the Chilean government to showcase the country’s fauna in various magazines and international fairs. It also became a semifinalist in the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition in 2011. Given the success of the image, I felt even more confident and comfortable with my style.

After a few years of continuing my studies in photography and tracking pumas, my feelings toward the animals and the way I perceived them in their environment gradually led to a change in my approach to photographing them. I no longer wanted just portraits or sharpness; I felt the need to capture the puma as the elusive, mystical feline it is. Those fleeting moments that remain only in memories and not in photos became more significant. Often, after days of searching and having a beautiful encounter with a puma, a single portrait couldn’t convey the full experience.

And it’s that very sensation I aimed to capture: a blend of how I feel walking in Patagonia while tracking pumas; the vulnerability I feel in such a vast, captivating, simultaneously hostile and beautiful environment. Gradually, I found myself more at ease when photographing pumas within the landscape. I began to think more about composition, seeking that angle that would allow me to balance the subject visually with its surroundings.

Atmosphere in Wildlife Photography

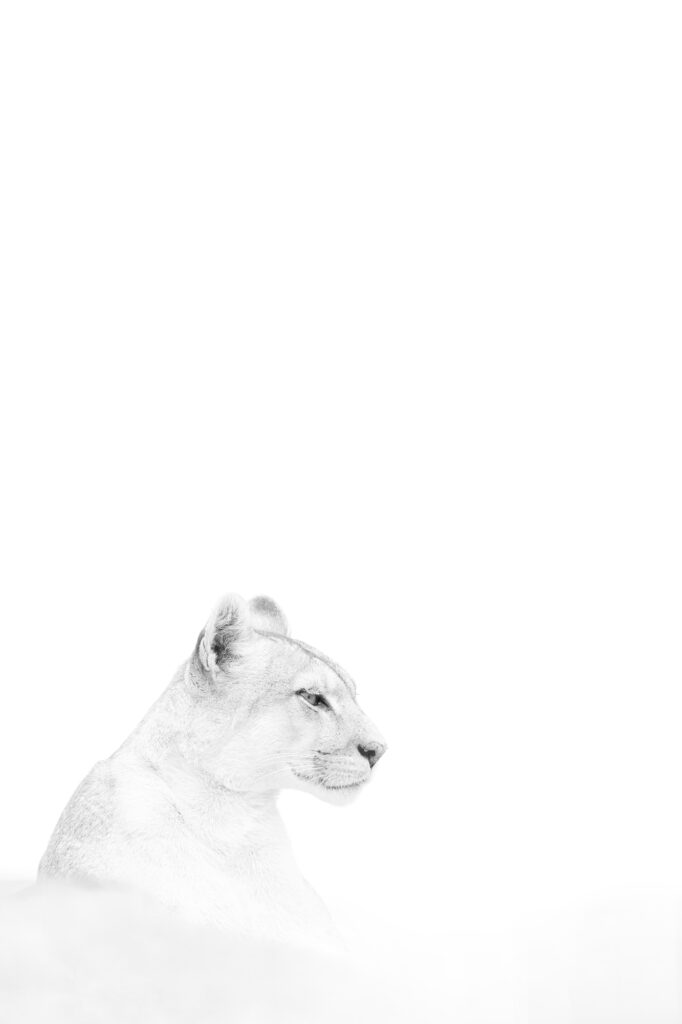

I’m deeply fascinated by the technique of combining intentional blurring with on-site, high-key photography. I believe it creates a uniquely delicate impression for the viewer. It’s this delicacy, or perhaps gentleness, that I personally feel this particular feline possesses compared to other big cats I’m familiar with, and it extends even to the possibility of walking alongside them. Sharing the same space without a physical barrier (like a vehicle) immediately establishes a certain bond between the photographer and the subject. To accompany a puma from a distance as you walk with it is a unique experience. It’s not always about taking photos in these moments; it’s the memory of walking alongside a big cat until it settles down to rest. Throughout this time, the puma accepts your presence, and then you can photograph it as it grooms, sunbathes, yawns, plays with its cubs, and so on. It’s during these moments that I’m drawn to create ethereal images, with intentional blurring, often using the grasses in front of me. I love placing the camera on the ground and focusing solely on the puma. In this way, I feel I can portray the puma as the true Ghost of the Andes

Tourism and Conservation

Today, puma photography attracts visitors from around the world to Torres del Paine. But many years ago, I was among very few people who came here to search for pumas. Along with the handful of puma trackers who were working in the area at the time, photographers and wildlife watchers could look for pumas both in the national park and on private estates where hunting these animals was still part of the culture, as it continues to be in other places not only in Chile but around the world.

In 2015, Estancia Laguna Amarga, which borders the national park and is home to a large resident population of pumas, reached an agreement with several puma trackers to regulate who could enter the property. It became the first estate to protect the puma and offer conservation tourism to various operators, as well as access for local scientists and world-renowned documentarians.

Today, after many years of collaborative work with scientists and puma trackers, the estate has established a management plan with protocols, regulations, and guidelines to ensure a safe and enriching experience for the wildlife, visitors, and guides.

For me, it’s an honor to be one of the puma trackers at the estancia. Not only does it allow me to photograph and guide in this area and follow the stories of several individual pumas who have remained in the territory for 10 years, but I also get to work with the property owners. I’ve learned much from them, and I’m deeply grateful for the opportunity to enter their estate and for the trust they’ve placed in my work as a professional and a photographer.