Three years in a row–2017, 2018, and 2019–I returned to the magnificent landscape of Patagonia to spend a month creating photographs. I was initially drawn to this region through the incredible images of photographers I admire, like Marc Adamus and Floris Van Breugal, showing its epic mountain peaks and crystalline glaciers in dramatic lighting. But what drew me to the area the most wasn’t necessarily the jagged granite faces of Fitz Roy, Cerro Torre, Paine Grande, or Los Cuernos that we see so often. Instead, I was more curious about the unique and beautiful lenga trees that are endemic to the area.

In the photographs I had seen of Patagonia, I was no doubt impressed by the one-of-a-kind peaks reaching up high into the sky, illuminated by stormy light, partially engulfed in dancing fog. However, I couldn’t help but notice how beautiful all of the colorful fall foliage was as well. I could tell the trees came in all different shapes, arrangements, and sizes, and displayed a dazzling array of rich vibrant colors. Whenever I would spot them in the corner of a photograph, I was left wanting to see more. To me, it looked like there were endless photographic opportunities and untapped potential in those forests. So when I finally made my first trip down there, I knew that I would be photographing the mountains, but my primary motivation was to show a different side of Patagonia; a side that until then had still been largely ignored by the thousands of photographers that flock there each year.

Waves and ice crash on the shore of Laguna Torre during a relentless windstorm.

Paine Grande breaks through the clouds after a week straight of being socked in with rain.

A fresh take on a familiar scene of Fitz Roy by finding a new perspective in a different section of this popular stream.

A unique perspective of Fitz Roy framed by fall foliage I found while exploring off the beaten path one afternoon.

Don’t get me wrong, on the mornings where there was dramatic atmosphere and light on the mountains; I too indulged in photographing the icons–while still trying my best to put my twist on them to make photographs that were mine, of course. But after my first visit in 2017, even though I had been there for a whole month and was able to ‘check off’ photos of all the famous peaks, I came home feeling like I hadn’t quite achieved my entire photographic vision.

This emptiness, this nagging feeling that I needed to do more, is what brought me back the next two years that followed. I had found a goldmine of photographic potential, as there were colorful, twisting, curving trees everywhere with so much unique character and large clumps of forest that I knew would look different each fall season. With such a broad range of subject matter combined with changing weather conditions and lighting, I was certain I could produce a much fuller body of work if I gave myself more time.

A dazzling array of fall foliage right off the main trail, still covered in morning frost.

And so I returned to Patagonia in the two years that followed, for a month again each time. With each trip, I made fewer photos of the mountains and more photos of the forests. The more time I spent observing them, the better I understood their nature and how I could portray them in my images. More ideas were born, and a special relationship grew–a relationship that I had yet to see in another photographer’s portfolio of Patagonia.

Inevitably, by exploring the area more and being open to other ideas, I found many other remarkable scenes, which also deserved to be photographed. Scenes like fallen leaves on a blanket of snow, ice in all different forms, and subtle lines and contrasts within the rugged landscape began to jump out at me everywhere I looked.

These three long trips that I made not only allowed me to create the portfolio that I now have of Patagonia, but the rest of my portfolio as well. I learned a valuable lesson from spending so much time in a popular area, drastically changing how I approach my photography.

A beautiful stand of lenga trees right off a popular trail that leads up to an iconic lake below Fitz Roy.

In Utah, where I have been living for the last ten years, we have some of the most visited national parks in the world: Arches, Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Canyonlands, and with good reason too; these places are undeniably unique and stunning. These days I can’t go anywhere without seeing dozens of nearly carbon-copy photographs of the iconic formations and vistas of these places. While it has always been obvious to me why so many people visit these national parks each year, I used to avoid them mainly because I believed there was nothing new to be done. I didn’t see any point in going to them to take the same photograph we’ve all seen hundreds of times in other portfolios and on social media.

It wasn’t until I came back from my first trip to Patagonia that I felt inspired to travel to the places near my home that I had been avoiding due to their extreme popularity. I believed that if I created the right environment for myself, I could come away with unique imagery no matter where I went, unlike the photographs we’d all seen before. So I started taking longer, slower-paced trips to these places. Sometimes I came home with an entire gallery of images from a single weekend; other times, I came away empty-handed, even on several trips in a row. I learned that creating novel imagery in popular locations is by no means an easy task, but it is definitely possible.

These are some things you can practice to create the kind of environment that’s conducive to finding scenes that haven’t already been photographed, even in the most popular locations.

Get Intimate

Excluding the context around a scene you are photographing by creating a tighter composition is one of the best ways to create a novel photograph. Often, by excluding the familiar elements surrounding the subject, viewers will have no clue where you even took the photo. The more you exclude around your subject, the fewer people will be able to tell that it was made in a well-known location. Thinking more abstractly will result in creating entirely new worlds altogether, completely independent of their location and setting.

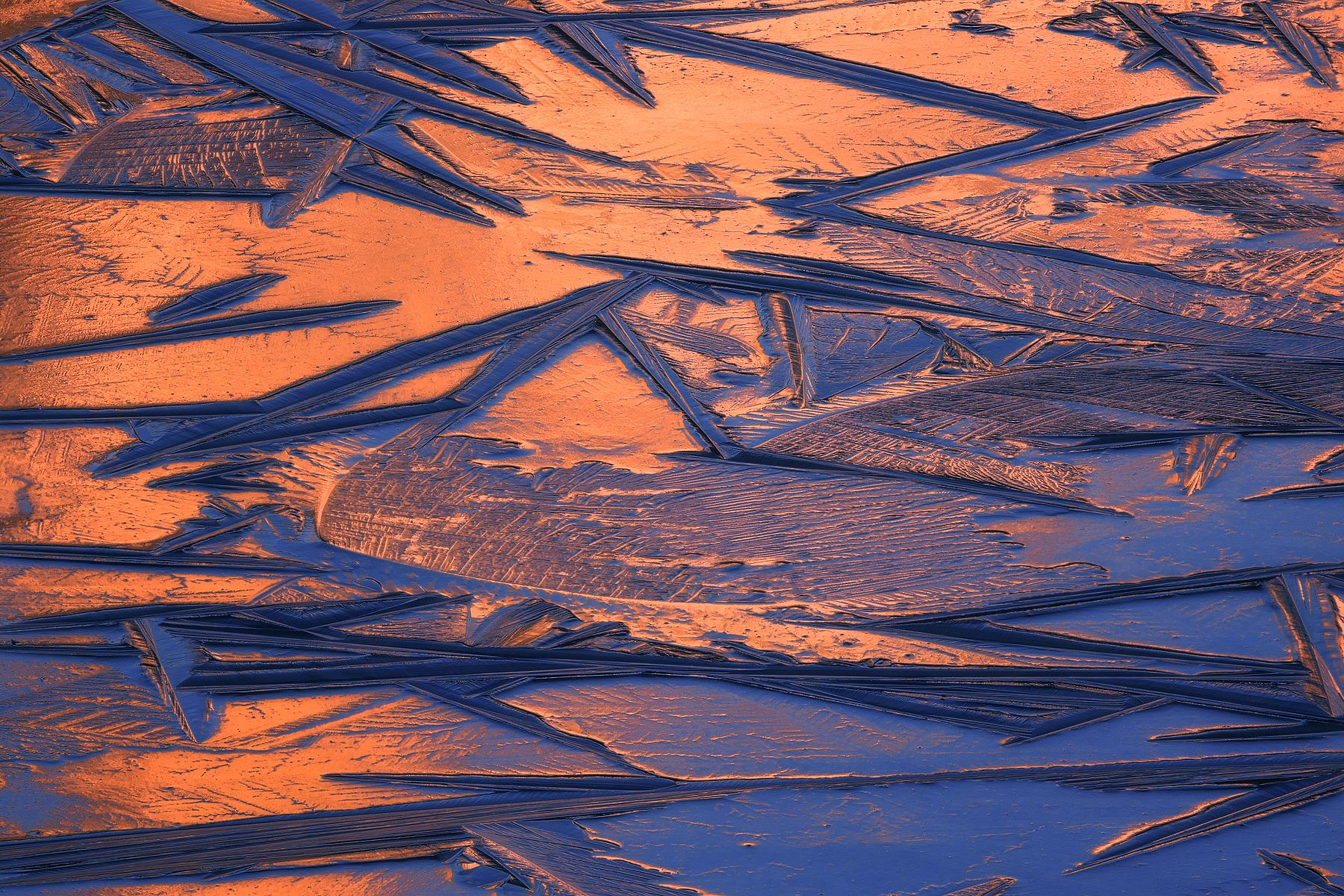

This doesn’t only apply to smaller, more macro scenes either. Even with trees, mountain peaks, or a waterfall, by isolating your subject a bit more and composing a little tighter, you can remove enough of its context not to reveal its exact location and make it feel like it’s from another place altogether. By practicing the art of exclusion, people would have no idea that I took these two scenes of ice patterns in a highly trafficked part of Patagonia unless I mentioned it in a description.

Fitz Roy, illuminated by red morning light, reflects in a small, frozen tarn a little ways off from the beaten path.

Fascinating lines dance across the surface of a small frozen puddle, right along the main trail. The rest of this remarkable puddle was smashed and broken from hikers trampling right through it.

“The world is rich in small wonders…but so poor in eyes that see them.”

– Glenn Wiggins

Allow More Time

Most icons are heavily photographed due to their easy accessibility, as harder to reach, more distant places tend to avoid becoming popular since they attract fewer visitors. If you are going to an iconic location, give yourself more time than just a single afternoon. By spending several days or even weeks in the same place, you will create the opportunity to get to see it in unique lighting and weather conditions, find new, subtler subjects besides the low hanging fruit that others have overlooked, and wander and explore more of the surrounding area to find things that other people haven’t had the time to reach and photograph. As you spend more time observing a place as the lighting changes throughout the day, you will also begin to notice things that didn’t jump out at you right away, giving you the capability to photograph less obvious scenes.

I spent a month camping in the same area on each trip I made to Patagonia. Having this extra time allowed me to explore all over and wander freely, without feeling pressured or rushed to make good photographs constantly. While longer trips have their challenges in terms of packing, enduring weather, and staying sane (anyone familiar with Patagonia knows about its notoriously brutal weather; on all three trips, I spent more days than not sitting inside of my tent waiting out relentless rainstorms–the longest stint was seven consecutive days), this was a crucial part of being able to create the unique body of work that I now have of the region.

An accessible yet overlooked waterfall right off a popular trail. I failed to notice this scene until about the seventh or eighth time I passed it and finally saw it in light that made it stand out.

Later in the season, after the crowds were gone, fresh snow blankets an iconic lake. Rare atmosphere, lighting, and weather conditions transform a familiar scene giving it a new and unique look.

Make It Personal

Like I’ve recommended focusing on more intimate compositions, it is also important to become more intimate with the place. Pay close attention to what you enjoy about the area. Do you connect with the iconic scene itself? Or is there another element within the landscape that speaks to you? If you can identify the specific thing you connect with in a location, you can focus on that and showcase it more concisely and powerfully. The specific things you connect with most likely won’t be the same things that the rest of the photographers notice when they visit. Just like how most people are drawn to Patagonia by the mountains, I realized that while the mountains are no doubt impressive, what spoke to me were the trees.

Sebastiao Salgado, a master of photography, has mentioned something several times in his books, autobiography, and presentations that has always stuck with me; to love your subject. If you fall in love with the places, objects, and ideas that you photograph, I don’t see how you could not come away with unique and personal images. Sometimes we fall in love with a location right away; it may require more time in other situations. Regardless, your love for something will grow the more you understand it. Read books about the places and things you are taking pictures of. Spend time in the places that you truly love, build your relationship with them, and you will inevitably create novel photographs.

While I loved seeing and photographing the iconic mountains of this area, what spoke to me were the endless tree scenes in the many forests below them. Experiencing all different weather and lighting conditions during the three months I spent there allowed me to create a full body of work that featured them in many different forms.

Going to iconic places and shooting them from the typical perspectives in predictable lighting is easy since it doesn’t require us to make an effort to come up with our own ideas. I think this is why we continue to see so many look-alike images coming from these popular places despite the endless opportunities they present for those who only wish to look a little closer, become more familiar, and walk a little further. While it is the more difficult approach in photography to create novel imagery in well-known places, I would argue that it is the most personally meaningful and rewarding. There is nothing like feeling you are making a unique contribution to the world by sharing something completely new.

Creating unique, personal, and novel photographs is also a great way to stand out in the world of nature photography. If people want to see a certain scene, license an image, or buy a print you have photographed, they will have to go through you, and only you, since no one else possesses it. The images you create wouldn’t be seen by the rest of the world if it were not for you. This will add tremendous value to your body of work for yourself and its viewers since it will be truly one of a kind.

If you’d like to see the rest of Eric’s portfolio of Patagonia, you can visit: www.bennettfilm.com/Patagonia