During my initial years of practicing nature photography–especially once it became my sole source of income–I did everything I could to ensure that I would come back from each place I went with ‘the shot.’ From pre-planning compositions based on predetermined subjects using Google Earth–figuring out exactly where I would stand and in which direction I would point my camera–to coinciding my visit with the moonrise or moonset in the perfect spot on the horizon. I would even come up with a shooting schedule for each location that included several different backup options and left no time for sleep. If the sunset was ‘bad’ then I would stay up to shoot the milky way, moonrise, or moonset over the same scene, or try again at sunrise, so that I could at least come away with something ‘usable.’

This went on for a couple of years until I eventually ran out of energy and became exhausted by these intense schedules I was making for myself; trying to pack in as many locations in a single trip as possible; loading up the car after sunset and driving through the night to make it to the next spot before the sunrise. At one point I was on a three week trip along the eastern coastline of Australia with a good friend of mine. It was my turn to drive through the night, dodging kangaroos, wombats, and wallabies, while he napped along the way. I fought my drowsiness the best I could but I ended up drifting off for a moment. I was abruptly woken up when one of the wheels of our small rental car went over the edge of the highway and I felt it tilt sideways. Holding my breath, I quickly jerked the steering wheel the other way and got us back onto the pitch black, windy road. Luckily, we made it to our destination a couple of hours later without falling asleep at the wheel again, as I was full of adrenaline from being scared to death.

On another occasion I wasn’t so lucky. After photographing sunrise at one spot, I quickly jumped back in the car and sped down a well graded dirt road that I had driven many times before. I was going as fast as I could in hopes to make it to another place that I wanted to photograph while the light was still ‘good.’ I was already imagining the next shot I would take in my head when all of a sudden one of my rear tires blew out as I was coming around a sharp, downhill corner, sending me sliding out of control towards a large wall of bentonite clay at 50mph. Trying to avoid the collision, I yanked on the steering wheel to change my trajectory and regain control. But to my horror, I was now flying sideways in the opposite direction with even more force towards something worse; a thirty foot drop into a dry wash. There was no stopping it now: my car was possessed and in full kamikaze mode. Before I knew it I went over the edge and the world spun like I was inside a washing machine, tumbling and rolling in freefall. The inside of my car was now a tornado of camera gear, camping equipment, and everything else that I had packed for my journey. As my life was flashing before my eyes, I thought to myself, “what a dumb way to go.” I was sure I was going to die.

After what felt like an eternity, I finally smashed into the hard, dry ground, making one last full rotation as glass shattered all around me and the horrific scream of twisting, bending, scraping metal rang in my ears. My poor SUV rocked around a few more times, finishing its death rattle before letting out a loud exhale and giving up its soul. Once everything became quiet, I opened my eyes in disbelief. I was still alive. My car was lying sideways on the passenger’s side. After some effort, I was able to push open the smashed, jammed door and crawl out. I stood and looked at the utterly mangled shell of what used to be my car, full of all sorts of rocks, dirt, broken glass, and debris. At that moment I had a crystal clear revelation: no photograph was worth my life.

I still continued to plan out my ‘shots’ but I stopped trying to pack in so many locations into each trip, no longer eager to rush from one place to the next. And so my travels became much more relaxed, which gave me more free time to leisurely explore and observe my surroundings while on my way to destinations. Not only did I enjoy these trips much more as they were way less tiring and more restorative–since they actually felt like a nice break from the busy day-to-day rush of normal life–I began to notice a pattern forming in my photography:

the images that I created out of pure spontaneity by photographing the unforeseen subjects, moments, and light that genuinely filled me with excitement were actually more meaningful and much more expressive.

Over time, this trend became so obvious that I decided to try completely letting go of any rigid expectations at all; purposely going to places without even a mental agenda or shooting schedule. My only intention and main priority when traveling to places was to enjoy my time there and experience them in the fullest way possible. As it turns out, I realized you can absolutely enjoy your time in a natural place even if it doesn’t yield a single photograph. To my surprise, not only were the images I was making much more personal–born out of a sincere fascination for the unexpected scenes I was encountering by being more open minded–I also became more prolific, coming back from trips with many more images than I ever did before.

It’s easy to see that being fixed on a certain goal, like making an image of a preconceived composition in very specific lighting, can blind us to other opportunities that may present themselves along the way–causing us to be too tunnel visioned to notice anything outside of our plan that doesn’t match our mental picture. But another thing I have realized is that pressure, which we can only inflict upon ourselves, is not conducive to creativity whatsoever, and only causes us to feel rushed and anxious to ‘get the shot’ instead of being in a calm, clear flowstate where time actually seems to slow down and we can closely follow our intuition.

Going out on a trip thinking that you need to make an image is just as silly as going to a party and thinking that you need to make a friend. Like great friendships, the best photos have a way of just happening all on their own. These special moments that make us excited enough to go through the effort to capture them in a photograph are completely outside of our control. We can choose where we go, what gear we use, where we stand, what we point our camera at, and when we press the shutter, but we cannot control what happens around us or what nature may present to us. Hoping to create a certain photograph no matter what, before you even arrive somewhere, is likely to cause you to try and force things to ‘work,’ which from my experience, never actually works.

If you are hoping to create unique, personal, and expressive photographs that are meaningful to you and those that view them, the best thing you can do is allow your creativity to come through as much as possible. Any kind of pressure, no matter what the cause is, will stifle creativity, and cause stress and frustration that will ultimately taint your experience in the place you visit.

If you don’t first have a meaningful experience yourself, you simply cannot convey one in a photograph.

Limited Time

One of the most severe sources of pressure is the feeling that we do not have enough time. If you have a flexible schedule, it is important to allow plenty of time for yourself in the places you visit (see “Creating Novel Imagery in Popular Locations”). Whenever I travel internationally or somewhere that’s very far away or difficult to access that I likely will not be able to return to for a long time, I always allow myself 2-5 weeks; this way I have more room for spontaneous exploration and more time to observe places, without feeling pressured to move on to somewhere else right away. On the other hand, if you have a full time job and can only get out to do photography a few times per year, this can make you feel like you need to make the most out of your precious time off from work. But packing the schedule with too many locations causes us to rush from one place to the next with no time to explore freely and follow our curiosity.

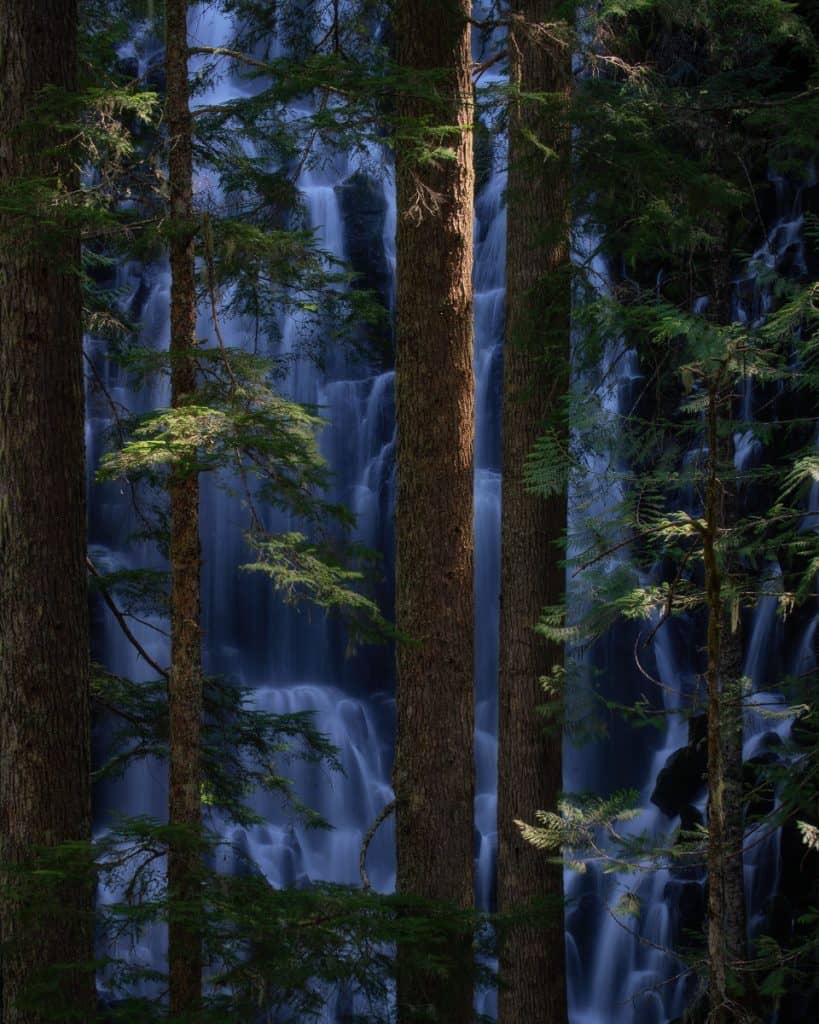

Also, if you are hoping to take lots of photographs during a shorter trip, going to many different places for only a brief window of time at each one will only yield photos of the kinds of things that are immediately obvious, providing these locations even have any kind of obvious landmark to begin with (this is why so many photographers that make quick visits to forests, where subjects are less pronounced, fail to create any photographs). You will also waste precious time while you are driving to each location that you could be using to create more images instead. Through years of experience, I know that going to more places in a single trip doesn’t necessarily result in more photographs, and I have actually found the opposite to be true: the more time I spend in a single place, the more images I return with.

If you only have a couple of days at a time to go out and make photographs, then I would encourage you to spend them in only one or two places, so that you have plenty of time to get acquainted with your surroundings and see them in all different kinds of lighting throughout the day. The more time you spend in a place, the more you will inevitably begin to notice besides just the obvious characteristics. This is when a lot of the quieter, subtler scenes will present themselves. This will also result in a better experience overall, as you may actually have a chance to connect with the place you are in and form a relationship with it that goes deeper than just its superficial traits.

Financial Aspects

From buying equipment to reaching locations, photography costs money and there is no way around it. I find the best way to not stress out about the money I spend on fuel, flights, rental cars, etc. and in turn feel pressured to make photographs, is to see it as investing in experiences and not things. After all, many of the photographs that I have taken on costly trips have now been removed from my portfolio, but it’s impossible for a day to go by without reflecting on past adventures that were truly unforgettable. For me, the photographs are just a byproduct of the experience, and not the end. This mindset makes every single trip I make worth the financial investment, regardless of the amount of photographs I come home with. If you find yourself feeling like trips are a waste of money, I encourage you to try using the quality of your experience as your metric instead of the quantity of images made.

As someone who has been a full time nature photographer for the past 8 years, I cannot stress enough how detrimental it is to the quality of what you create when you are doing it with the sole intention of making money. Making nature photography your career or sole income should be done first and foremost so that you can dedicate your life to spending time in nature and practicing the craft of photography.

As soon as you begin to practice photography with the primary motivation to make money from it, your authenticity, ethics, and ideas will become distorted, and most of all, it becomes more stressful, since an outing that doesn’t produce photos will feel like a waste of your time.

Instead of feeling like you can take time to explore each place in a carefree manner, you will be more inclined to only spend as much time as you need to be able to ‘get the shot’ and try to collect as many images as possible in each outing, in order to get the most profit from your energy. You will also be less inclined to go to lesser-known locations where it is harder to anticipate that you will be able to make a ‘great’ photograph. The pressure to create images that ‘will sell’ will also cause you to only focus on certain kinds of scenes, and you will be less likely to use your time experimenting and making more personal photographs that others may not connect with.

Feeding Social Media

Maybe you feel like you need to constantly post new work on your website or Instagram in order to stay relevant and on people’s minds. And maybe even more so if you are depending on photography for your livelihood. Feeling like you constantly need to create new images so you can always be posting because of a quota you have set for yourself will create pressure to make as many images as you can on each trip you go on. This can cause you to scramble around in each location as you frantically try to photograph everything you can, instead of spending more time observing your surroundings and letting things speak to you, or dialing in your compositions.

If you can instead become perfectly okay with the idea that you may come home empty-handed, this relieves a tremendous amount of pressure to make images, and instead of forcing yourself to take pictures, you will only take pictures when absolutely necessary: when something calls your attention or speaks to you so strongly that you can’t help but pull your camera out and photograph it. These situations tend to make for the best images, since your excitement is more likely to come through in the scene and excite the viewer as well. Ironically, once you free yourself from the pressure of having to create images entirely, you will be more likely to create a greater quantity of images since your creativity will flow more freely.

Returning to Familiar Places

The places I feel the least amount of pressure to make photographs in are ones that are close to my home, where I can easily return again the next day, or several times in a single season. Since there is little investment necessary of time, energy, and money to reach nearby places, this accessibility causes us to feel like we have virtually unlimited opportunities to create images, and also less anxious about returning home empty-handed. These are great places to experiment and try out new things, which in turn will help you grow. And as a result, you might even make some images that you really like! Some of the most memorable experiences I have had while out making photographs were in rather ordinary (at least to the typical tourist) natural places very close to my home.

There is great value in becoming familiar with certain places, by returning time and time again. Not only is it very special to build a relationship with a natural place and have it begin to feel like home, knowing a place like the back of your hand can yield a tremendous amount of images through extensive exploration as you look closely at its every nuanced detail. Having a deep familiarity with a place also helps alleviate stress when you do encounter once-in-a-lifetime lighting or weather conditions. Rather than scrambling around to look for something that works, you can head directly to a place you already have in mind that you know will be complemented by the remarkable lighting.

Understanding Light

The most popular sunrise or sunset lighting, which is too often termed ‘good light’ in photography, lasts for only a brief moment. Knowing how quickly it will be gone can cause anxiety and fear of missing that moment by not finding a good composition in time, which in turn will only harm any chance you have of being creative with your camera. On the other hand, the better you can understand light–and the advantages and unique effects of each different quality of natural light that you can encounter–the more you will be able to effectively use the light at any given time of the day.

There is no such thing as bad light, only good or bad uses of light.

Learning how to utilize more ordinary lighting such as harsh midday light or overcast soft light– that is more constant and less fleeting–will allow you to photograph subjects in peace, not feeling like you are racing against the clock.

I can recall many times when I was focused on only shooting during these short periods of the day, waking up already stressed out that the conditions might not line up quite right, or that I might not find a great scene to pair with the ephemeral lighting. Now that I spend time in nature in a more carefree way, I understand that good light isn’t only present for a brief moment in each day. I don’t ever feel like I am going to miss the light, since I am certain there will be plenty of other opportunities of perfectly usable light to follow. Nowadays, when the sky explodes with vibrant, rich colors at the beginning or end of the day, I don’t even worry about making a photograph most of the time. I just sit and enjoy it instead, since I realize it doesn’t actually complement the scenery in front of me. Don’t rob yourself from enjoying these remarkable moments in nature for the sake of trying to make a photograph. If trying to shoot during this short timespan is stressing you out too much, just put the camera down. It’s okay.

On many occasions, when I have hung around for a while after shooting the sunrise at a location, long after all the other photographers have already gone, I have noticed that the light that best complemented the scene actually occurred hours later. Of course I am not saying you shouldn’t bother making photographs during sunrise or sunset either. Rather, I want to point out that this short window of the day is definitely not your only chance to create something bold, evocative, and meaningful. By all means, capture these moments, but there is no need to feel like you have to ‘get something out of them’ or else the whole rest of the day is wasted.

Great Images Aren’t Always Epic

Many years ago when I first began photographing more intimate scenes, I shared a concern with my mentor, David Thompson, that they didn’t feel as impactful as the other grand landscape images that already dominated my portfolio. His response was that not every image we take needs to be mind-blowing, and a portfolio often benefits from having quieter, more subtle scenes to balance it out. In galleries, art directors are aware of something called ‘visual fatigue’ and they purposely place simpler images in between more shocking, saturated, or complex ones in order to not wear out the mind of the viewer and make them numb to the rest of the images. This kind of variety also makes a body of work more interesting to look at, instead of feeling repetitive (see “Creating a Diverse Portfolio”).

I have since learned to appreciate both the variety of images in my portfolio, as well as the variety of expressions and landscapes that we can find in nature. Now, I don’t ever try to look for any certain quality of scene; rather, if I find something that fascinates me because it is beautiful, strange, hopeful, despairing, simple, complex, comforting, disturbing, serene, dramatic, mysterious, etc. then I photograph it. Nature has so many sides to it that are even more prevalent than just the ‘perfect’ moments that seldomly occur. Give yourself permission to photograph these quieter, subtler scenes as well.

Also, if you are just hunting for obvious, epic, grand landscapes, you will be severely limited to the kinds of places you can photograph in. Sure, you may find these kinds of scenes in iconic places like Patagonia, Yosemite, or the Dolomites, but you may as well write off forests entirely, and you can forget about shooting interesting patterns in dried mud, subtle designs in the sand, or an abstract reflection on the rippled surface of a pond. Being open to photographing all different kinds of scenes will not only take away the pressure of needing to find that one particular shot, but you will also build a more diverse portfolio and become a more well rounded photographer. More importantly, you will develop a much fuller relationship with nature as you learn to appreciate it in all its different forms.

A memory that comes to mind is a trip I made to Grand Teton National Park many years ago. On a day that the light was ‘boring,’ another photographer and I went to some trails in a less popular area of the park and hiked around all day in hopes of finding a unique angle of the impressive mountain peaks with some kind of interesting foreground–maybe a curving stream or a lake with a nice reflection–hoping to create a new, epic scene. Looking back, I can still remember this hike fairly well, and I can imagine all of the marvelous scenes we hurried past while hunting for that specific kind of photograph: lily pads floating in serene ponds; interesting reflections of trees; patches of colorful wildflowers; stands of vibrant aspens. It was also a partly cloudy day so there were plenty of options in terms of lighting. But all of these potential scenes that could have made for great photographs were written off entirely, because they did not fit the description of the scene we were looking for. I’ll also add that we never did find that scene we had in mind.

Although this has been my attitude towards visiting natural places for the last five years now, on my most recent trip, I found myself slipping back into my old ways of thinking, and the ghost of my past-self began to eat away at my mind once again.

After many years and thousands of miles of rallying my trusty, compact sedan down rough dirt roads that most people would think it has no business being on (and never having a single issue or flat tire I’ll add), I finally invested in a fairly new 4×4 truck so that I could reach more remote places. As many of you may know, buying a car right now is not cheap, as prices have skyrocketed due to supply shortages and manufacturing issues caused by the pandemic. Gas prices are also prohibitively high (currently $5/gallon here in Utah at the time of writing this), so being as frugal as I am, this first trip in my new truck felt especially expensive.

Because I had to invest so much more money than usual into this five day trip to my favorite area, I once again felt pressure to make great images. My mind kept saying “you better make this worth it, Eric” and “I can’t believe you spent all this money to come down here and not take any good photos.” I looked through my guidebooks to try and decide where to go, already judging places based on single images and brief descriptions, without ever having seen them in-person, in order to go somewhere that seemed the most ‘promising.’ I was also overwhelmed with all of the new areas I could access that I had been dreaming of exploring for years. And so this desire to go everywhere all at once caused me to rush from one spot to the next just a bit quicker than I normally do.

When it was time to return home, I had in fact made a few images that I do enjoy, but I can’t honestly say that it was the most enjoyable experience overall. Instead of coming home feeling refueled and restored, I was exhausted. It seems I also need to remember my own advice at times. I guess it’s true what they say after all: old habits die hard.