It dawned on me a couple of years ago that my skills and knowledge in photography — and worst of all, my images — had stagnated. I was in a rut, and I didn’t see an obvious way out. Part of this was just because of me, and part was because of my job.

Day to day, my job involves testing camera gear for the website Photography Life, especially cameras and lenses. I mention this because it’s omnipresent in the types of photographs I end up making. To illustrate each review, I aim for about 20-30 photos, and the photos need to cover a wide variety of subjects. I love the work, but I’m sure you can see some of the creative pitfalls at play.

In particular, 20-30 photos per review is a high bar. I love taking meaningful photos as much as any photographer, but for most reviews, I’m happy if each picture meets the standard of “good” or simply “publishable.” I even tend to visit the same few locations over and over, just because I know them well enough to get something to post.

That’s not a recipe to capture photos as a meaningful form of art. My ever-growing Lightroom library has more than 70,000 photos, most of them lousy, and I’m increasing the volume every month.

It eventually dawned on me that taking any given photo no longer felt special — and how could it? Once I took one, I needed to move onto something else, or risk delaying the review. In essence, it’s the trap that Eric Bennett discussed in his NPN article, The Perils of Pressure. When photography is your job, it takes effort for it to remain your creative outlet, too.

That’s where the theme of this article comes in. Today, I’ll introduce the thought process and approach to photography that dragged me out of the rut and helped me capture more meaningful photos over the last year. The most important thing I learned is to keep one thing in mind as a photographer: giving the photograph a reason to exist.

The Cost of a Photograph

One of the unique things about photography is that it costs very little to take a photo. Some cameras are expensive, but photos — at least digital photos — are not. A digital photograph isn’t made of decadent slabs of marble or costly paints on a canvas. Pixels are essentially free.

Even the price of printing a photograph is unusual compared to other art, since photographers usually only print work that’s already good. A photographer can take 10,000 bad pictures, take one good picture, and print it for $25. A painter cannot paint 10,000 bad paintings without a huge financial outlay.

In a way, this is what attracted me to photography in the first place, since I started as a high schooler with barely enough savings for a basic camera. It is still, to me, one of photography’s biggest strengths. Four out of five people across the globe have a smartphone camera, making photography one of the most accessible art forms in history.

Another unusual thing about photography is how quickly you can take a picture. I’d imagine that most photographers reading this article have already taken more than 10,000 photos, whereas very few painters, sculptors, or digital illustrators ever produce that much work — good or bad — in their entire lives.

The low cost and fast pace of photography can be nice, but there’s also a trap: the cheapening of a photo. In most forms of art, failure is time-consuming and expensive. In photography, taking hundreds of bad photos in a row is just an ordinary Tuesday.

Don’t get me wrong; I don’t want each photo to cost more money to take. Just the opposite. I hope that storage devices and top-quality cameras continue to become less expensive over time, so anyone will have access to the tools they need as a photographer, regardless of their budget.

But I do believe, in order to produce better work, you need to consider your photos as being worthy of time and effort. It doesn’t matter if the actual cost is low; don’t think of a photo as throwaway. Instead, slow down, and consider each picture as if it were an important — and yes, even costly — creation.

This doesn’t just apply to landscape photography. It can be more difficult in fast-paced genres like macro and wildlife photography, but I still recommend approaching each photo as a valuable thing to capture. It’s all too easy to fire off a haphazard burst of high-FPS pictures in the hopes of getting something that’s in focus… even when the photo won’t be a keeper no matter how sharp it is.

In short, if you keep in mind “the cost of a photo,” you’re more likely to get things right in the field. It’s not always the approach you need to take in photography — sometimes going faster and sorting everything out later really is the right approach — but when you have time, and the scene in front of you is promising, make each photo count.

Deliberate, Thoughtful Composition

I’ve always been a proponent of putting thought into each photograph rather than leaving its appearance to chance. Hopefully that’s common sense. If you close your eyes, spin around, and point your camera vaguely in the direction of a mountain, the photo is going to have severe flaws. Instead, if you consider your composition thoughtfully and take your time, the mountain is nearly certain to look better in your photo.

Continuing the example, if you want the best photo of the mountain, there’s still more you can do. Instead of moving on after the composition looks better, take the time to evaluate the qualities of the subject, especially the emotion that it conveys. How can you accentuate those qualities? What is the best time of day, and the most suitable weather, to convey the mood of the subject?

This process involves asking yourself questions, including the ones I just mentioned. It also involves looking for flaws in your photos and correcting them when you can in the field, rather than leaving everything for post-processing. It’s a pretty active form of photography.

A good way to express things — even if it’s a bit of a cliché — is the difference between “taking versus making” a photo. Anyone can see a subject, point their camera, take a photo, and move on. It’s a surefire path to filling a hard drive with snapshots, and maybe you can hope for a few winners when you sort through them later.

The harder process is to scout for the right location, think about the emotions of the subject, decide upon the best time and conditions to return, consider any distractions in the frame, and capture a deliberately-composed photo.

I’m sure most photographers will agree that the second approach is going to have a higher keeper rate. Even if you skip the scouting/returning steps (maybe you’re traveling and those aren’t feasible), there is always room to put more thought into a photo, especially into your composition.

Unifying Your Message

If creating a deliberately-composed photo sounds good, but you don’t see how to put it into practice, maybe you’ll find the following approach useful. I call it “unifying your message.” It’s the methodology I’ve landed on after lots of trial and error.

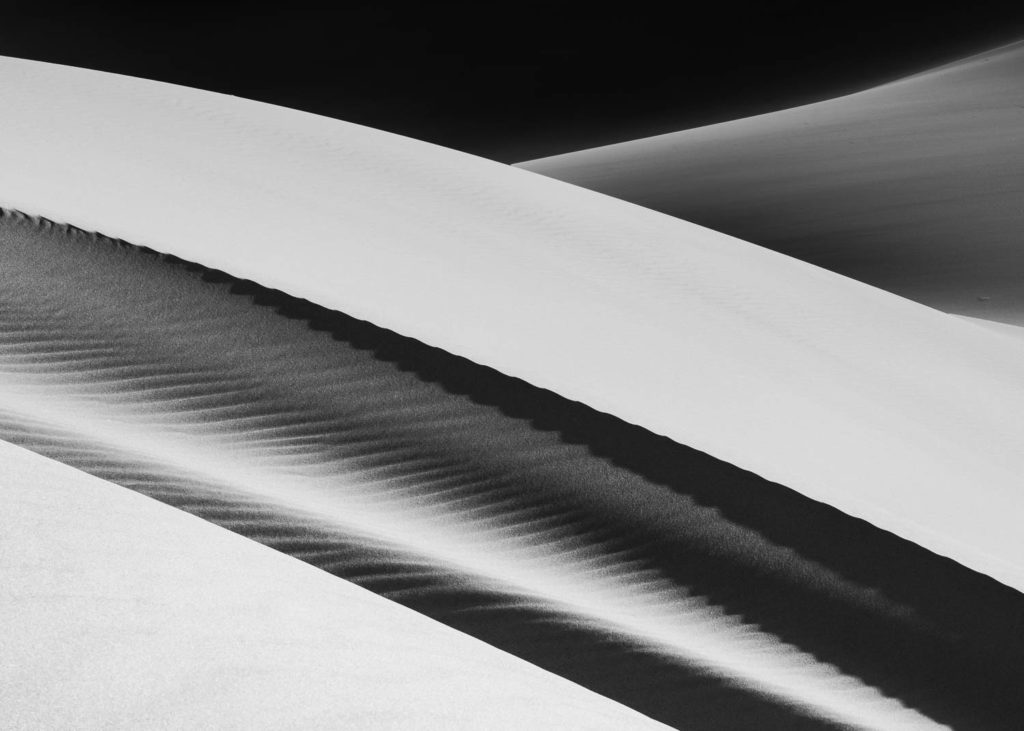

The idea is simple: Each subject in photography possesses its own emotional qualities. A rocky, jagged mountain peak is intense and harsh. A tall redwood tree has the qualities of grandeur and peacefulness. The winding curve of a sand dune has gentle and hypnotic emotions — and so on.

With your photographic decisions, as I hinted at already, you can accentuate these qualities. There are tons of tools at your disposal, including the balance/imbalance of your composition, positive and negative space, and (if you’re willing to wait or return later) the light and weather conditions at hand. Beyond that, you can also exclude objects from a photo that take away from this message, such as recomposing the photo to avoid harsh footprints in a gentle sand dune.

In other words, try to match the subject’s emotions to the emotions imparted by your photographic decisions. It’s why I have no reservations about ignoring the so-called “rule” of thirds and placing my subject in the center of the frame if I want more balance, or right at the edge of the frame if I’m after deliberate imbalance. Likewise for any other rule of photography. Instead of checking the boxes of a composition template, it’s better to spend your energy focused on a photo’s emotional message.

Putting this approach into practice can be fairly easy, but it requires conscious thought and doesn’t happen by accident. As a hypothetical example, consider the subject of a lone pine tree in a field. How could you emphasize that quality of loneliness and isolation?

In this case, you can return on a foggy day or during a snowstorm, when all the details in the background will be obscured. You can then frame the composition to make the pine tree very small, with a blanket of empty, negative space covering the rest of the photo. You can even imbalance the composition, placing the tree off to the side instead of the center, to give the photo a more tense feeling.

All of these decisions would unify the photo’s message. You would end up accentuating the subject’s existing qualities of loneliness and isolation. And — to the title of this article — you would give the photograph a reason to exist.

Why the Photograph Exists

Each time that you capture a photo, you’re creating something. It won’t always be a work of art, and that’s all right, but it remains important to take (or make) your photos for a reason. That’s at the heart of all three topics that I’ve discussed so far.

It starts with keeping in mind the cost of a photo. For my own landscape photography, I go so far as to use large format film most of the time, in part because it forces me to slow down and never forget the importance of a photo. Even if you don’t take such an extreme approach, at least stop thinking of each photo as a cheap or worthless thing to create. When you capture a photo, you’re making something of value. It’s worth slowing down and getting things right — and learning something each time a photo turns out poorly, just like any other form of art.

After that, put deliberate thought into your compositions. Don’t settle on the first snapshot that you could take in a matter of seconds. Instead, embrace the old cliché and make your photos. The best way to do this is to ask as many questions as possible when you’re in the field. Are you standing in the best spot? Is anything blocking important subjects in your photo? How does the light look right now, and how do you think it will look later? And so on. It’s not impossible to take good photos by luck and volume, but deliberateness usually gets you much further.

Finally, consider the best way to unify the photo’s message. Every subject carries its own emotions, which you’ll only notice if you slow down and think. Once you recognize those emotions, you can take the process to its conclusion. The goal is to match the emotions of the variables you control — composition, timing, camera settings, post-processing, etc. — to the emotions of the subject. Unify them as much as possible. And, before you press the shutter button, exclude anything from the photo that conflicts with your message.

I believe this process makes it easier to take photos that mean something and have a reason to exist. It’s not the only way to take good pictures, but it’s the most effective method that I’ve found. Giving each photo “a reason to exist” has also helped me climb out of the slump, improve my photos, and even help me enjoy photography more. Photography is at its best when it’s a process of creative expression and art.

Still, nothing in life is absolute. I love the slower process, but with my job, I still need to prioritize volume over quality in many cases. Otherwise, any camera reviews I write would only contain a few pictures. What matters instead is when I take personal, non-work-related photos. When I do, these days, the biggest thing I think about is a reason to exist. Not only do I take higher quality photos with that thought in mind, but I also get more fulfillment out of photography and creating something meaningful. I hope that you find the same is true for you.