Nature Photographers Network was one of the few resources online back in the early 2000s where one could find genuine content about photography, and I remember a membership there was my first investment into learning the craft. Almost 21 years since that time, I recently got an invitation from NPN to write a little about my photography, and it was a surreal kind of feeling. It took me back to where it all began for me. From wanting to be a landscape photographer to a tiger photographer to a bird photographer, I have taken my time learning the ropes of photography and more importantly learning about myself.

What I photograph and how I photograph reflect a lot about who I am in real life, that much I am sure of. I can’t say this for everyone, but for me the easiest way to be creative about photography has been to look at it as a medium to express myself.

Sometime back in 2017 is when my photography journey changed track: from being obsessed about shooting birds on clean perches to making images that had more of myself in them. I attribute my change in part to advancements in camera gear. Everything started to seem easier to do with the newer cameras. Until that time, I was so engrossed in the technical that I feel my expressions took a back seat. Over the past six years I have found a new medium in wildlife photography, one I can use to communicate. Or so I feel at least.

As I started reading about photography I was more and more drawn towards minimalism, and I have been trying to keep that as my guiding light. With minimalism as a constant, I started exploring more of what calls to me. I believe this was a critical step for my journey as a photographer to really begin.

Like most of us who love nature, I am very drawn to its day-to-day marvels: falling snow, pelting rain, dust storms, the setting sun, and so on. These marvels work as fabulous canvas for wildlife photography. I dream of shooting in a dust storm, for example, or shooting in heavy, foggy, misty weather. I am like a child in a candy store when I am greeted by bad weather, and that’s when I probably get my best frames as well. True, bad weather comes with its challenges; but that’s where it gets fun. I feel incomparable joy when I am out there making frames while nature is expressing itself.

I’d like to take your attention back to minimalism to explain my approach towards wildlife photography. Take a pause and answer this for me: What is minimalism to you?

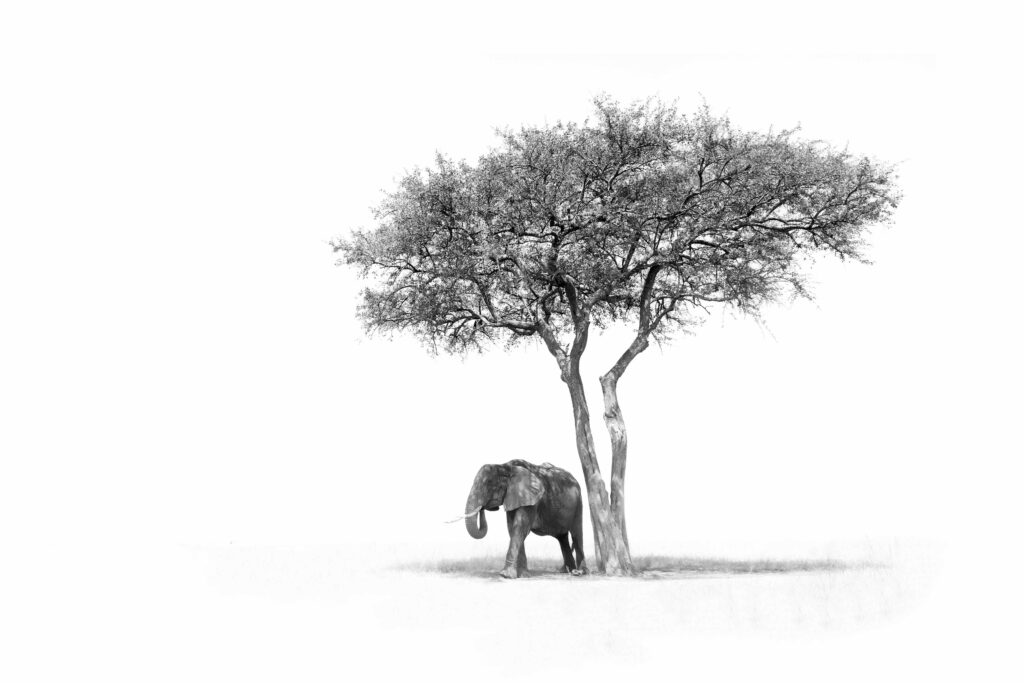

I feel it can have a different meaning for each person. My interpretation of minimalism is probably slightly different to the way it is defined in the books. To me it means less conflict in the frame. That’s a definition that works well for my mind, and most of my imagery is heavily influenced by it. I was drawn to black-and-white or, increasingly, monotone and duotone images, mainly because they help me achieve this lack of conflict in the frame. Less conflict means I can better draw the viewer’s attention to what I want to convey.

Nowadays I love to make images that leave something untold. In the fast-paced lives that we live, an image that makes you pause and think about it is probably an image that works. At least those are the kinds of frames — ones that are open to interpretation, open to debate — that work for me. I find myself increasingly looking for compositions where I can leave the viewer with a question or at the very least a thought.

To achieve this, there are four techniques that I generally call upon.

Shooting Into the Light

This technique is the lowest-hanging fruit in creative wildlife photography, but it is undeniably one of the surest ways to make visually arresting images. These might not necessarily be images that ask a lot of questions or add a lot of mystery, but they will cause that pause.

Over the past few years, this has been my default style. I don’t really remember when I began actively going after front-lit scenes. I have found myself shooting into the light or using sidelight even when the sun is hidden. For example, I find that shooting into the light, even on a cloudy day, is the best way to highlight rain; the same would go for dust and snow.

Use That Foreground

This is probably the technique or style that comes most naturally to me. It is a highly underused but very effective tool. The foreground can be kept in focus or out of focus, and I am equally attracted to both. Be it leaves, grass, reflection on water, fire, snow, or something else — an out-of-focus foreground just adds such a lot of drama to the image. I like it when the foreground sort of obstructs the main element in the frame yet leaves room for enough of the subject to attract attention.

In-focus foreground is slightly tougher to work with, but I like the way it adds weight to some frames. It has an in-your-face feel to it. One that you cannot ignore.

Slow It Down

Success might be a little difficult to achieve with a slow shutter speed, but the technique can be highly effective for asking questions or drawing attention. We have all done a little bit of panning in wildlife photography, but these days I find the best slow-shutter images are when the subject and camera are not moving in sync. You could be using the fascinating technique of Intentional Camera Movement, or your subject could be moving, or both; done right, these images have the power to draw you in like nothing else. I look forward to exploring a lot more of this in the coming years.

Shoot White or Shoot Black

In common terms, I mean high-key or low-key frames. It took me a while to start seeing these in the field. By seeing these, I mean identifying opportunities. I still struggle a bit with this, and I hope to improve. When I have been able to see the possibilities, I have found a lot of satisfaction in making this kind of image, whether of mammals in the middle of the day taking rest under the trees of the Masai Mara or of black birds against a black background. When I get these frames right, I feel a different kind of high. These generally are not accidental: You need to go looking for them (or at least I need to).

These days I am trying to mix and match the four techniques, like shooting low-key with ICM, or shooting backlit with foreground blur to try and see how it ends up. Not all images turn out as you thought they would. Most are disasters; some work out okay.

If you have made it this far, I am sure you are wondering if this guy shoots only monotone or duotone images. I really don’t think I set out to shoot only these tones, but I feel they help my narrative more than other kinds of images. I don’t have a rule that says when I go for black-and-white and when I stick with colours. It is more of an internal process for me. If I feel that what I want to convey will come out better in these monotone or duotone images, I’ll go for them.

I have to say, though, that over the course of my journey I have developed a liking for these styles. I am not 100% sure if this is the path I will stay on, but let’s hope I’ll continue to try. Wildlife photography as a genre has opened up a lot in the past few years, and I hope that I’ll keep evolving with it as well. For now, I am super-excited about my path. There is just so much to unlearn, so much to try.