Okavango! The name itself conjures up fantasies of southern Africa — animals around waterholes as dust clouds roll in from the parched Kalahari plains. But this hot, dry, arid version of the Okavango is only the summer half of a fuller, richer story. One of the few delta ecosystems in the world that don’t flood into the sea, the Okavango Delta in northern Botswana fills with winter and spring rains from the Angolan highlands to the north and, in the summer, dissipates into the sands of the Kalahari Desert before evaporating as an inland delta.

The “dry Okavango” is the one most often seen in photographs. When the annual drought sets in, the animals gather en masse around the few waterholes, creating endless photographic opportunities. But my hope as a wildlife photographer is always to find something unexpected and different, which led me to wonder, “If everyone goes to the Okavango in the summer/fall, I wonder what it’s like in the winter/spring?”

The answer? The desert gives way to a lush, green, watery wonderland. Given all the photographs I’d seen of the summer Delta, it was completely unexpected, and everything I’d ever heard about the Okavango became untrue. Animals were harder to find, but when I did find them, the experiences were extraordinary.

For example, what we typically see in photographs of hippos are their backs and the tops of their heads sticking out of the water in a crowded hippo pool. Patience is a virtue at those pools; I try to get there early when the light is soft and wait for interesting interactions like the image of two young males play fighting. The cooler weather and the temptation of the green grasses occasionally draws them out of the water for longer periods in the morning. This extended time on land can lead to unusual views, such as a low, front angle of a hippo that emphasizes its bulk.

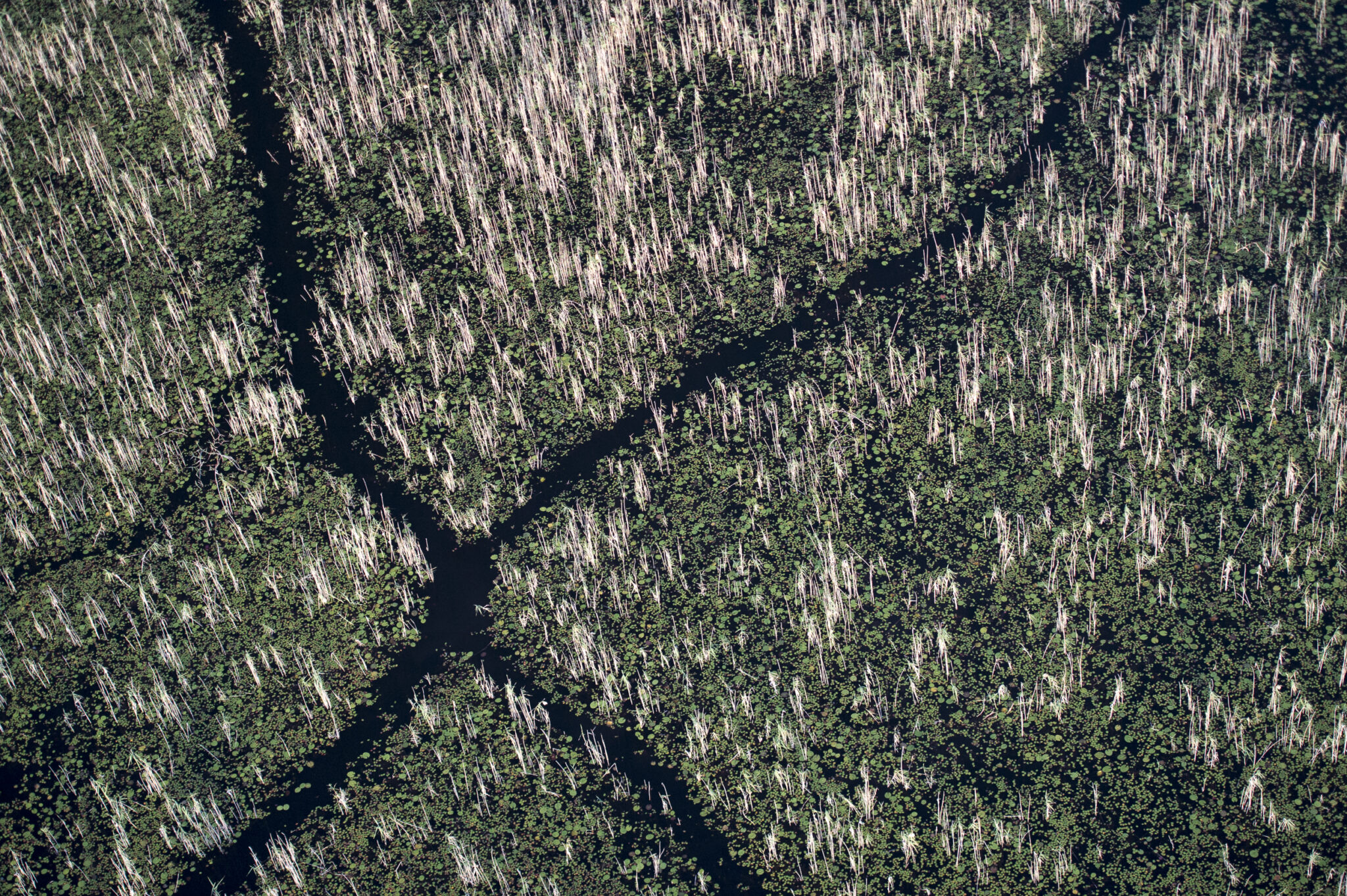

To create an image that was more connected to the Delta I looked for a way to photograph from the air. This allowed me to create abstract patterns from the trails that hippos make as they cut through the lilies on their way in and out of the water. While drones are illegal in Botswana’s wildlife areas, light planes and helicopters are available for hire. I recommend a 100-400 mm lens and a shutter speed of 1/1000 or faster for this. These settings offer multiple composition options and a fast enough shutter to counteract aircraft vibration.

Telling the Story

Beyond the resident subjects, when photographing a specific place I always try to find scenes that are iconic to that location. In the Delta, I focused on the lechwe, an aquatic antelope that spends most of its time in knee-deep water and feeds exclusively on water plants and reeds. Their feet coated with a water-repellent substance, red lechwe quickly dash through the marshlands to escape predators, an action that makes them beautifully photogenic. A reddish-brown animal amid green grasses and blue water provides endless possibilities.

I initially shot the usual animal portrait images before asking myself what made the lechwe unique to the Okavango and how I would tell that story. I chose a low point of view for my first image of a group of lechwe feeding on a floodplain surrounded by tall grass. The result of that effort showed what made the animal unique, but it wasn’t particularly charismatic. One of the magical things about lechwe is how they run through grassy flood plains and become airborne when they encounter a water channel. And I knew I wanted to capture that.

Exercising Patience

After observing the animals for a while, I had an image in mind that I felt would tell the full lechwe story: good light, green grass, a clear water channel, and a reddish-brown antelope suspended in midair. It was a solid idea, but the execution took days. I’d locate a herd of lechwe, see which direction they were headed, and find a channel they would jump over. After many attempts, all the elements came together a few times. I not only made the image I initially hoped for, but also made an image with multiple antelope in the air. And because I was shooting at a high frame rate, I was able to capture a series of images of a single jump that I merged into a composite photograph. Patience doesn’t always pay off, but when it does, it makes it all worthwhile.

Some encounters, like the lechwe shot, can be planned. Others involve some degree of luck and spending a lot of time. African wild dogs (aka “painted wolves”) are one of the world’s rarest predators; habitat encroachment, human-wildlife conflict, infectious disease, and the changing environment are threatening the survival of the species. So while I hoped I would see one, I didn’t expect that I would — and I certainly didn’t expect to find a pack of wild dogs attempting to stalk a giraffe, picking a fight with a pack of hyenas, and finally playing in a mud puddle in gorgeous late afternoon backlight. I felt like I should burn my cameras afterward because I would never get to photograph anything that magical ever again.

My goal was to show what was unique about the Okavango, but I also made sure I photographed the animals that aren’t unique to the Delta: the long shadows of antelope from above, elephants playing in the water, leopards in trees, and lions running in the long grass. Not only does this help tell a well-rounded story of this wonderful part of the world, but it helps to create a stronger body of photographic work overall. It also creates opportunities for surprises — like a leopard eating a baby leopard tortoise!

Despite feeling that my time photographing the wild dogs was the ultimate, as-good-as-it-gets experience, I’m looking eagerly forward to going back to see what the Delta offers the next time; I know these extraordinary places are never exactly the same when you return. So the only burning question I have about the Okavango is, “How soon can I get back there?”