Introduction

Observing the natural world as a 9-year-old was, for me, one of exploration and mystery. I was fortunate to have grown up in a large parkland estate surrounded by all kinds of wildlife. The 105-acre lake was a haven for birds in winter and insects in summer. I spent most of my school holidays exploring and watching the dragons and bright blue damsels congregating in their masses along the margins of the shoreline. Little did I know then that these enigmatic creatures would be the catalyst many years later for a career change, leaving a hospital profession in dentistry to pursue one with a camera.

Brachytron pratense

I have always been fascinated with dragonflies from an early age. I have studied them scientifically for 30 years and have written a lot about their behaviour and ecology including two publications. They are without doubt one of the most popular insect groups among photographers. I prefer to photograph them with longer lenses equipped with an extension tube to reduce the minimum focusing distance. Early morning is still the ideal time of day.

Nikon D800, 300mm f/2.8 + extension tube @ f/11 ISO 100

Two photographers who were a big influence on me at that time were Stephen Dalton and John Shaw. Dalton is an English wildlife photographer, author, and a legend in the world of high-speed flash photography. He turned his lifelong passion for the natural world into a highly successful career. Insects, reptiles, birds, and mammals have all been immortalised at 1/30,000sec under his custom-designed high-speed flash units, which he still uses today, some 40 years on. His superb depictions of insects and other natural history subjects set a pictorial and artistic standard that is still respected today. Even with the advances in camera technology, much of his earlier high-speed flash imagery has never been bettered. I felt privileged when he wrote the forward in one of my first photography publications. The other photographer I followed at that time was an American called John Shaw, one of the most respected natural history photographers in the world. A legend in the states and a highly successful author and creative nature photographer who had a particular passion for macro. He has photographed on every continent and his work has featured in numerous books, and some of the most prestigious natural history magazines around the world. He is synonymous with the Nikon brand and not surprisingly they chose him as a featured ‘Legend Behind the Lens’ in 2002. Shaw’s ability to create something visually eye-catching and pictorial from rather ordinary subjects was one of his many skills. His books are still a source of inspiration today even 30 years on.

Rana temporaria

Working with flash to freeze motion and capture subjects in action was a lot more challenging pre-digital. It required flash units capable of very high flash durations, but with a large light output and a complicated array of beams and triggers. I spent two days trying to capture the moment frogs entered the water for an up-and-coming book publication. Getting the right posture and keeping the subject in the frame and in focus is the most challenging part of this type of photography. Some 200 images later I managed to get the shot I was after.

Nikon D810, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/11 flash ISO 200

Gonepteryx cleopatra

Nikon sent me the Z9 in early December 2021. While running a workshop in Northern Spain in 2022, I wanted to see if I could capture butterflies in flight, free hand while they moved from flowerer to flower. Being incredibly fast, trying to predict when the insect would take flight was the challenging part along with keeping the subject in focus. You missed far more than you captured in the frame. However, it was incredible that you now had technology capable of achieving this.

Nikon Z 9, Z105mm micro nikkor 1/4000 sec @ f/11 ISO 2000

As a professional Natural History Photographer, I have undertaken many different projects from hanging out of helicopters to working and photographing in the subterranean landscape documenting some of Ireland’s well-known cave systems. However, Macro has always been one of my main specialities and I have devoted many years to this particular genera having studied and photographed both in Ireland and in Europe many diverse insect groups, including the flora and fauna of different regions from the Alps to the Mediterranean. Today many years on as a photographer, the natural world for me is still a source of beauty, discovery, and inspiration. My enthusiasm for it has remained with me throughout my life.

Anacamptis pyramidalis

It has often been said that static subjects present less of a challenge photographically. I find flowers incredibly challenging; you have to work that much harder to achieve something that is graphically strong and pictorial. I frequently shoot with long lenses photographing through foreground foliage to create a soft ethereal result.

Nikon D850, 300mm f/2.8 @ f/8 ISO 125

Deilephila elpenor

Butterflies and moths are another insect group of interest to me. I have travelled and collaborated with many people around the world and have been lucky enough to have photographed many different species from different countries. The Nikon 200mm micro nikkor is my most frequently used macro. I tend to shoot quite a lot of subjects with this lens. Having a greater working distance along with a narrow angle of view helps greatly with background control.

Nikon D850, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/11 ISO 100

Understanding Macro Terminology

The word “Macro” is a term frequently misused by many, including camera and lens manufacturers who use it loosely to describe a close-up facility on a lens, mobile phone or compact. The definition of macro photography (‘Photomacrography’) in the true sense relates to magnifications from 1:1 (life-size) to around 10:1. The boundaries of where Photomacrography ends, and Photomicrography begins are often confusing as there are different definitions depending on what you read. The definition of Microphotography is different again and relates to photography using a microscope and is normally defined as images taken from 20:1 upwards.

Photographing subjects below life-size is generally referred to as ‘Close-up Photography, which is the category that the vast majority of photographers and their images fall into. However, for this article and to reduce confusion I will use the word ‘macro’ in the general context when discussing close-up photography.

Xanthoria parietina Parmelia sulcata & associated species

One of the advantages of macro is the wealth of subject material around you. Even the tiniest branches have whole communities living on them. In this case lichens and mosses. The vast amount of imagery in macro falls into the category of Close-up Photography since most of the photographs are normally taken below 1:1 or life-size.

Nikon Z 9, Z105mm micro nikkor @ f/11 ISO 200

Evolution of Macro

Those of us who are fortunate to have an interest in the smaller world are privileged to see and experience a microcosm of beauty and mystery, most of which is beyond our normal field of vision. For the masses who go about the daily routine of life, it’s a world unfamiliar to them. They see only the big picture and are, for the most part, oblivious to its importance in maintaining the ecological equilibrium on our planet.

Macro photography today has evolved considerably since the 1980s. Historically it was deemed by many to be a niche or specialty, practised by those with an interest primarily in insects, plants and to a lesser extent marine fauna. That was perhaps true to a point when you look back to the 1970s and 80s. Most of the photographers then were widely acknowledged as specialists in their respective fields. Some had or came from a natural history background, their photographic careers in most cases developed from their specific interests.

Spilosoma lubricipeda

My knowledge and understanding of moths have helped me considerably in getting acceptable images of these amazing insects over the years. I came across this beautiful little moth by chance very early in the morning. It had been resting overnight in a small patch of emerging willowherb. Gardens are often a haven for many types of insects.

Nikon D850, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/11 ISO 100

When the digital revolution hit, it was a milestone in the photographic world and marked a change not only in how we work but also in how we produce images today. Like many photographers, I eventually embraced it, but not quickly. As a committed user of medium format and an Ambassador in the UK for Mamiya at that time, I held back, not willing to part with my beloved Mamiya’s and Fuji Velvia that quickly. It took me a while to convert, and I waited until I felt digital could give me the results, or, at least, close to what was possible with medium format.

Pyrrhosoma nymphula

One of the most attractive damselflies. This image was taken over 25 years ago on my Mamiya RZ67. Despite its age, it remains one of my favourite photographs from the days of analogue capture. It was used as the poster image for the launch of the Dragonfly Ireland Project funded by The Southern and Northern Ireland governments.

Mamiya RZ67, 140mm macro lens @ f/11 Fuji Velvia

Iphiclides podalirius

Pre-digital I used a pair of Mamiya 645 PROs for the majority of my macro work and the RZ67 mainly for landscapes, but were possible close-ups if the subject permitted. Bellows systems were much more cumbersome to use then, and very little high-magnification macro was done in the field. These butterflies were feeding on the Red Valerian in a small hotel in the French Alps. It was just a question of waiting until some were in a suitable position to photograph.

Mamiya 645 PRO, 120mm macro lens @ f/11 Fuji Velvia

Gastropacha quercifolia ab. daimatina

A rather unusual moth and one of my favourites from my Fuji Velvia days. I loved this film and still frequently look at some of the images on my lightbox from all those years ago. Although digital brought many new techniques it sealed the fate of analogue capture and had a profound effect on the professional side of the photographic industry.

Mamiya 645 PRO, 120mm macro lens @ f/11 Fuji Velvia

The world of macro pre-digital was perceived by many as a combination of magnification ratios, flash exposure calculations and working to very precise procedures. Reversing standard and wide-angle lenses on bellows to achieve greater magnifications was all part of the macro photographers kit at that time. TTL (‘through the lens’) flash was available in some cameras but in a rudimentary form. Shooting active subjects at magnifications beyond life-size in the field was, for the most part, challenging and restricted mainly to the studio. As photographers back then most of us were running on Fuji Velvia, which was the standard transparency film, both in the amateur and professional sectors; an amazing product, but like all transparency films totally unforgiving if you got the exposure wrong. Many photographers new to macro found the whole process perplexing, especially when working with living subjects that were frequently less than cooperative.

Today macro has seen its popularity rise among the masses. The continual advances in mobile phone technology have, to some extent, been a contributing factor. Acceptable images can be achieved on these devices with little knowledge and effort. However, having said that, DLSRs and mirrorless cameras are still the ideal choices for many reasons. Their versatility, wide selection of lenses, resolution and the use of specialist equipment cannot be equalled, even with the best mobile devices. The rapid progression in mirrorless technology, coupled with the latest advances in post-processing software makes it possible to photograph and depict subjects in ways that were simply impossible to achieve with film. Butterflies, moths, insects, and flowers are now seen in a whole new light. Their colours, structure, and form provide a wide range of possibilities for those that are looking for a fresh perspective or perhaps a change in direction to their photography.

Cercopis vulnerata

One of the biggest advantages of digital was being to analyse your images in the field. Any shortcomings meant you could reshoot while in situ until you were happy with the result. This was a turning point for me especially when photographing and running workshops in Europe, as I could check in advance to ensure I nailed the shot.

Nikon D3X, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/16 ISO 200

Improved Workflow Performance

Since the evolution of digital photography, advancements in software development have seen many new techniques and workflow improvements become available. There is a plethora of programs out there that will offer you a complete workflow system. The rapid expansion in Raw processing especially in the last few years has made it possible to overcome many of the time-consuming procedures and issues that were once tedious several years ago. For example, digital editing, selection, and captioning have been greatly improved, with many software programs undertaking some of the laborious aspects, which were often repetitious. Captioning multiple images and inserting additional metadata is all possible with a few clicks of the mouse. Improvements in ISO values means very acceptable images are now possible with only marginal differences in dynamic range and image quality. Managing digital noise has also seen major enhancements with programs such as Topaz AI streamlining the process.

GPS is an important aspect of my routine photography and provides valuable information on sites and specific location data on rare and endangered plants, this is an essential requirement for me, especially when working in other counties. It is also helpful when photographing from helicopters allowing you to pinpoint precisely where you’ve been shooting from. Having an integral GPS makes it much easier for me to caption locations in other countries and when shooting from the air. Thankfully my Z 9 has it incorporated into the camera. I would have purchased the camera alone just for this one feature. Nikon’s GP-1 unit (an obvious afterthought) was, for the most part, frustrating to work with having gone through several cables.

Neotinea ustulata

A beautiful little orchid and one of my favourite species. It was part of a small group growing in a single location on top of the San Glorio Pass in the Cantabrian Mountains in Northern Spain. GPS comes into its own when recording locations for rare plants and insects. Five years later I was back in the region running a workshop and was able to go to the exact location where these plants were growing.

Nikon D2X, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/11 ISO 200

I can’t overemphasise the importance of having a proper systematic digital workflow program. It will not only speed up the editing process, but it’s also adding important information to your images turning each of them into a valuable resource and photographic record. You may not initially see the relevance of doing this now but 30 years on photographs can provide valuable information to environmental agencies on species that were once present in that area at the time. I have already seen the benefits of this in some of the work I did on dragonflies over 20 years ago. I have a comprehensive digital asset management structure which I implement for every shoot. I am always amazed by how many photographers lack any sort of organised structure to their editing and storage of their digital files. I have written about this before and given a simple workflow example in my latest macro book. I am, by nature, meticulous about image data since most of my photography ends up in the libraries of various government organisations. My natural history collection will eventually be archived in the national museum. A detailed captioned image is as important as a set specimen in the cabinet of a museum. A photograph nice as it may be lacks any real value if devoid of information or a story in my opinion.

Techniques to Overcome Classic Problems

There are many issues to consider, in macro photography. Reduced depth of field is perhaps one of the biggest to contend with. Photographing considerably smaller subjects means having to work at much closer distances compared to routine conventional photography. The zone of sharpness is therefore greatly reduced as magnification increases; in some cases, it’s down to millimetres. Retaining sharpness throughout the subject being photographed depends on two factors, magnification, and the aperture value. Choosing a smaller aperture of f/16 or f/22 for example does not necessarily guarantee complete sharpness throughout the subject, magnification also has a bearing on depth of field in the final image. Diffraction is another issue to contend with particularly when working at smaller apertures in addition to having to select slower shutter speeds or higher ISO values. These are age-old problems and were just as prevalent in the pre-digital days of analogue capture. Digital has provided solutions to some of the classic problems that macro photographers face. The most notable of these is the ability to extend the depth of field by combining individual images using specialist software to produce a single composite image commonly referred to as ‘Focus Stacking’. Recent editions of Photoshop allow you to do this but in a more rudimentary way. It has limitations in what can be achieved compared to specialist software programs such as Helicon Focus and Zerene Stacker.

Mycena inclinata

While searching a decaying stump, I found this nicely arranged group of bonnet fungi. Selecting a small aperture would not have been sufficient to keep all of the group plus the background in focus. Diffraction would also have been an issue in reducing contrast and sharpness. This type of situation is one that lends itself to focus stacking.

Nikon D850, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/8 ISO 400 Composite image

Extending Depth of Field or Focus Stacking

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss focus stacking in any detail. I have devoted considerable time to this technique over the years testing it with many different setups and combinations, especially at magnifications beyond 1:1. I will address this in more detail in a future article as there are many different approaches to it. Most methods produce an acceptable result below life-size but are much less effective at magnifications beyond 1:1. Having said that I will give a brief overview of the basic principles.

Focus Stacking, Focus Blending or Extended Depth of Field are terms used to describe the digital image processing technique. A series of images photographed at different focus distances are combined to produce a final photograph that has a greater depth of field than any individual source image. The collective images are then processed in a specialist piece of software which analyses and blends the in-focus areas within each image to form the final photograph. One of the advantages of applying the focus stacking technique is that you can shoot at the lens’s sharpest aperture, or sweet spot while retaining maximum detail and contrast in the photograph. You can also photograph subjects from more oblique viewpoints; something that would have been difficult to achieve working pre-digital.

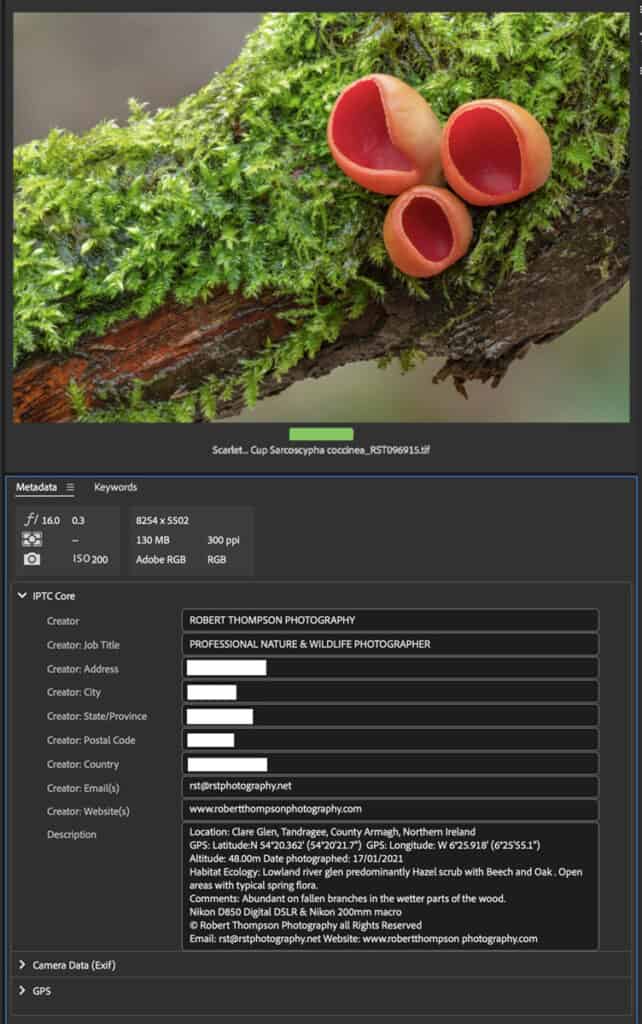

Sarcoscypha austriaca

Being able to take advantage of shooting multiple images to extend depth of field and combining them in specialist software has been a major game changer in macro. It gives you the freedom to compose and photograph subjects from more oblique angles. Something that was not easily achieved pre-digital.

Nikon Z 9, Z105mm micro nikkor @ f/8 ISO 200 Composite image

I should point out that focus stacking is not the answer and solution for every image that lacks sufficient depth of field. If that were the case, we would end up with a series of photographs that are uniform in appearance and lacking in imagination and style. It should be used carefully and creatively when the image would benefit from its application. It is not always necessary to have complete sharpness throughout a photograph for several reasons. For example, you may want to create an artistic interpretation, and in this context, the choice of aperture and focal length of the lens are important and dictate how the final image will look. Also, photographing mobile subjects such as insects presents a greater challenge when employing the focus stacking procedure. Trying to capture multiple images of a moving creature brings its own frustrations. In my own work, I use it when I think the subject will benefit from it or when working at higher magnifications when sharpness and resolving detail throughout is the most important aspect of the image.

Some camera manufacturers have incorporated a focus stacking feature within some of their cameras utilising the autofocus system to move the lens to different focus points as dictated by the parameters set by the photographer in the menu. However, this approach is of limited use, in my opinion, and best suited to images captured at lower magnifications since you have no control of the autofocus during the stack sequence. It can also be a bit hit or miss; also the degree of focus overlap is limited compared to an automated rail. Focus stacking is best carried out with autofocus switched off, where you have complete control of the whole process. I do not use the inbuilt focus shift in any of my recent Nikon’s. I much prefer to use other methods to obtain a composite image.

Pieris napi

I have pointed out that focus stacking is not the ultimate answer for every image. However, when used effectively and in the right situation, it can add that extra dimension to your work. There are many situations where I do not use it, for example, with mobile subjects. Sometimes shooting with a wide aperture and through the foreground, vegetation creates a highly pictorial result, as in this case.

Nikon Z 7II, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/4 ISO 100

A Final Word

The photographic world at present is in a continual state of flux. New products, devices and accessories appear almost daily. Technology is moving so quickly it’s sometimes hard to keep abreast. The future of photography as a business is challenging but also exciting. Macro photography in the past may have been seen as a specialist field with limited interest, but that’s no longer the case; it’s come a long way, and its popularity has grown immensely in recent years and continues to do so. Digital is certainly the reason, and the latest improvements in camera phone technology will drive that interest even further. The largest publisher of images is now the web; it provides a platform for all photographers (irrespective of their skill level) from around the world to share and exhibit their images with fellow photographers. The bulk of photographic business now takes place on the web, and that will undoubtedly increase in the future. Social media dominates the photo industry and is an important part of the business. It does not, however, define your skill or ability as a photographer, but being in the social media domain is one of the most important parts of your business.

The way photographers experience nature photography, be it macro or wildlife, is also different than in the past. The most obvious change is access to a plethora of workshops currently being offered. Photographers are taken specifically to a location to photograph their subjects or in controlled conditions where it has already been set up to a point. The downside is they acquire little to no experience in researching their subject or doing their own fieldwork. Does the result merit the same accolade as someone who has done all of the work himself? It’s not a criticism but merely a point worth stating. The question to ask is how much of what we achieve today is down to technology or individual skill and ingenuity; I think there is much more ambiguity now between both. Making your mark today in the digital world is perhaps more challenging than in the days of analogue.

Manduca sexta larva

An impressive species belonging to the hawk-moth family. These creatures tend to be highly sensitive to vibration. For successful results, it’s best not to touch the branch they are on. That often starts them wandering all over the branch making it much more difficult to achieve the shot.

Nikon D850, 200mm micro nikkor @ f/11 ISO 200

The process of creating successful images, irrespective of where your photographic interest lies, is still the same as it was pre or post-digital. It’s a combination of research, technical know-how, a creative mind and above all patience. As photographers, none of us would claim to produce visually eye-catching images with every click of the shutter. Light, composition, lens selection and an interesting subject form the core of a great photograph. Getting all these elements into a single image is challenging, even for the most accomplished photographers. For those that can amalgamate artistic vision with technical competency is the key that separates them from the rest. The photographic bar is high these days, and making your mark is perhaps more challenging than ever. Learning from other talented photographers in the field is important, but develop your own style and aim beyond what has already been accomplished!