Is yelling the only way to be heard?

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, Heavy Metal was my favorite genre of music to listen to. Growing up as a teenager, my friends and I would push the poor stereo to its limits, blasting Slayer as loud as we could while driving around in my dad’s car, headbanging, yelling, and blowing out the speakers. Whether we were going skating, getting food, or just on our way home, it would get us pumped and make us feel alive. There were bands out there that understood us, what it felt like to be an outsider, to be angry at the world, and so we listened. Any metalhead knows there is only one acceptable volume for rocking out, and that’s cranked up all the way!

What separates Metal from other musical genres is that right off with the first chord, instead of slowly building, most songs start at 100% speed and volume (if you want to see what that sounds like listen to “A Corpse Without Soul” by Mercyful Fate). From there, the volume and fast tempo are maintained as loud as it goes all the way until the end of the song where it usually ends abruptly like running into a brick wall. Play as hard and loud as you can from the very start to the very end. Even bands like Metallica tried to record the ‘loudest’ albums ever, by using equipment that could record the instruments plugged into powerful amplifiers at their highest levels. For a long time, Metal followed this trend while in this sort of ‘noise war’ to see who could punch it up the loudest.

By now, you’re probably saying, “Wait? Wasn’t this supposed to be an article about photography? Where am I?” I know, I know, I’m three paragraphs in, and you’re scared this is going to have nothing to do with how you can take prettier pictures. Or maybe this is sounding all too familiar, and you are already making the connection on your own. Just stick with me here, I am about to make a face-melting point! While the photography medium doesn’t have a ‘volume’ slider, it has its own kind of noise, especially when thrown into the fast-paced world of social media, where thousands and thousands of visuals are trying to steal our attention every minute.

Because of this, I see a lot of photographers falling into the same kind of ‘noise war’ where they crank up the color, saturation, light, and subject matter, all in a desperate attempt to say “Wait, don’t look over there! Look at me!” Trying to demand someone’s attention by yelling at them can be effective, but is it the best way to keep them listening? Just like nowadays when I will occasionally break out the old records (really meaning just searching on Spotify) and rock out to some ol’ Heavy Metal classics, my ears can only last through a few songs, like most normal people, before they get fatigued. In the same way, I can only be on Instagram, 500px, and Facebook, for a few minutes before my eyes become tired from visual fatigue.

When you think of a quieter photo, what comes to mind? Probably a photo of simpler subject matter, maybe more abstract, without an obvious composition. It’s probably not as colorful or even black and white, doesn’t include as many objects, and requires more time and attention to understand and digest. Now, I’m not saying that you should not crank up the volume and shoot crazy light over big scenes that call for including more objects and being a bit more liberal with those photoshop adjustments. No, not by any means. I am trying to point out that if you continually play one note, at one volume, always portraying the world in the same way, eventually you are going to tire your audience, and most likely burn yourself out as well, rubbing the senses raw.

When I look through a photographer’s portfolio, the thing that makes me decide on following them or not, keeps me coming back for more, and impresses me the most, is that they have a wide variety of images in their gallery — ranging from very loud and powerful to very quiet and subtle. Looking through a gallery of images all cranked up to the same volume gets tiring, boring, and monotonous. After a while, it just feels like the same image, taken over and over again in a different place. This is why I feel that creating a tasteful portfolio takes some skill. For a body of work to be compelling, visually pleasing, and continually interesting from the first image to the last, there needs to be a lot of variety from each image to the next in scenes, lighting, processing, simplicity, mood, and color. This demands much more from the artist rather than letting them play the same note time and time again, merely repeating what they know best.

It’s true, the crazier, louder, and more ‘epic’ scenes will probably grab more attention on social media. But is that all there is to creating art? Is it just all about getting others’ attention by any means necessary? Well, have you ever thought about what you want to tell them once you have their attention? This is why today it is even more important than ever to know what your purpose is with sharing your images. If you are caught in the ‘noise race’ of trying to grab attention wherever you can, you will find yourself always looking for the same kind of crazy scenes and cranking the sliders to +100. You can only go so high, and so you will eventually plateau there, with nowhere else to go.

If you have found yourself stuck with your head at the ceiling, not seeing any more ways to outdo yourself, I have good news! You always have somewhere else to go! Back down. Take some time to explore areas you are less comfortable in, thinking about scenes you have never tried to shoot before, lighting that you usually write off as ‘bad,’ using lenses you have yet to experiment with, techniques you haven’t yet mastered. There is nothing more exciting, like trying something new! Don’t let yourself get caught in the ‘one-trick pony’ mindset, find your limits, and go past them. It’s the only way to expand your artistic abilities. It’s also the only way that doing the same thing for years and years can remain interesting. So many photographers fail to do this, which is why so many drop off after just a couple of years. They’re burned out from trying to keep up in the wrong way.

From my experience, the smaller, simpler scenes are what have caused me to grow the most as an artist, and better understand principles like composition, lighting, and color. Making something compelling within a smaller area or with fewer objects to combine is naturally more difficult, and you have fewer crutches to lean on. It is harder to hide imperfections when you are zoomed in on the details. Your mistakes become more noticeable both to yourself and your viewers. Because of this, you will probably fail more often than when shooting the big, more iconic scenes with epic sunset skies. The quieter scenes have nothing else to rely on besides your creativity and skills. But with each failure, we learn something new, and over time, with enough determination, you will begin to figure it out and see the world differently. Like anything, the increased difficulty also causes increased satisfaction when you do succeed.

Quiet photography, instead of yelling at people to look, sits, and waits. It patiently stays hidden until those who are truly seeking something different, something more profound, come and find it. This is where the artist’s personality can stand out and be felt by the viewer. Not by what you do like everyone else, but by what you do differently, (“Your art is not to be found in the things you do like other people, but in the things you do differently than other people.” – Guy Tal) and that will create a special connection with all those that understand your imagery. These kinds of deep connections with peers and fans are much more rewarding to me than the superficial, shallow imagery that tries to appeal to everyone.

So how are you supposed to know when it is more appropriate to let the image be loud and intense or quiet and subtle? It all depends on the scene in front of you and how it speaks to you. An image that comes to mind from my portfolio is a photo from my first trip to Patagonia, Argentina, back in 2017. It was an extremely windy morning and waves, some a meter high, were continuously breaking near the shore on a big, glacial lagoon. The waves were causing pieces of ice that had calved off the glacier to rock around as they violently crashed against them. There was also intense light hitting the peak and surrounding clouds. Initially, I pulled out my telephoto and was trying to shoot more intimate scenes concentrating on the breaking waves and icebergs, but this wasn’t allowing for enough context. It could have been a picture of waves on the ocean, in somewhat ordinary lighting. What was making this moment extraordinary was the fact that there were big, powerful waves breaking, not in the ocean, but in a glacial lake, high up in the mountains, something we rarely see, even in Patagonia. The only way I could portray this to the viewer was by including the rest of the scene.

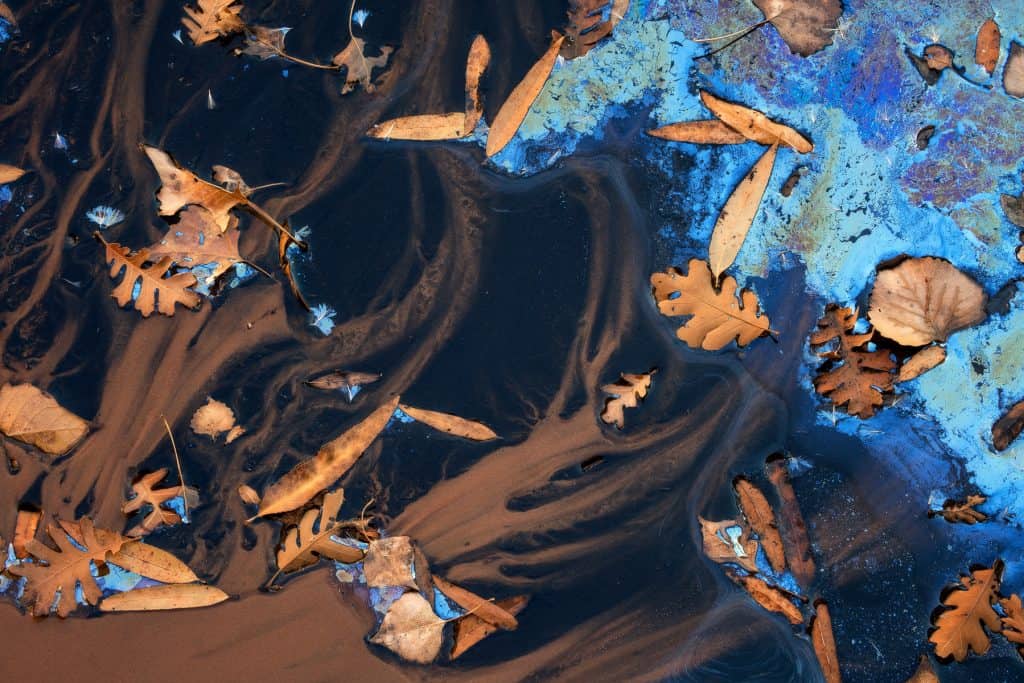

Sometimes you will find details that are better appreciated by themselves, removing all of the context of where the photo was taken, time of day, lighting, and even scale. This allows the viewer to dive deeper into the details and causes their imagination to run wild, wondering what else could be around the scene, or if it continues on forever. Including any other objects would only dilute the image and distract the viewer from focusing on the small details that you have decided are most important. The best choice is to amplify them, put them right in the viewer’s face, and not allow them to look elsewhere. Some images that come to mind are my pictures of leaves in puddles covered with biofilm. They give no suggestions to the size of the puddle, where it was shot, or during what time of day. It is also difficult to tell what focal length they were shot at, which allows the viewer to go deeper into the scene, not distracted by thoughts of a photographer taking the photo. There are certain scenarios, as a photographer, where it is of paramount importance to not betray your presence.

Ironically, if you think about it, the people who we usually listen to are not those that scream the loudest or that demand attention, that’s childish. The ones that talk the most are most likely to be ignored and avoided, while the ones that rarely speak and choose their words carefully are those who we are more anxious to hear from. What kind of artist do you want to be? The one that has to shout and shout, until they lose their voice? Or the one that is sought out by true admirers that are willing to devote more of their time to appreciate their work?