Editors Note: This is a special guest post from one of our longtime NPN members Max Waugh, who was recently bestowed the honor of winning Wildlife Photographer of the Year in the Black and White category. Please give Max your congratulations!

On February 7, 2018, I was driving my clients through a snowstorm in Yellowstone National Park. We were part-way through my winter photo tour, and it had been a fun week so far. My clients were awesome… friendly, enthusiastic and fun. These are all qualities I hope for in a group, as my job becomes that much easier when everyone’s getting along and striving for the same goals.

In this case, I only had four people in my vehicle (my maximum on winter trips), a couple of Americans and a couple from the United Kingdom. During our week together we happened to chat a lot about photo contests… specifically Wildlife Photographer of the Year. A winner of the “Emerging Talent Portfolio” WPY award (soon to be a two-time winner), whose work one of my UK clients admired, was in the park at the same time as us, so we naturally talked quite a bit about his work and the competition.

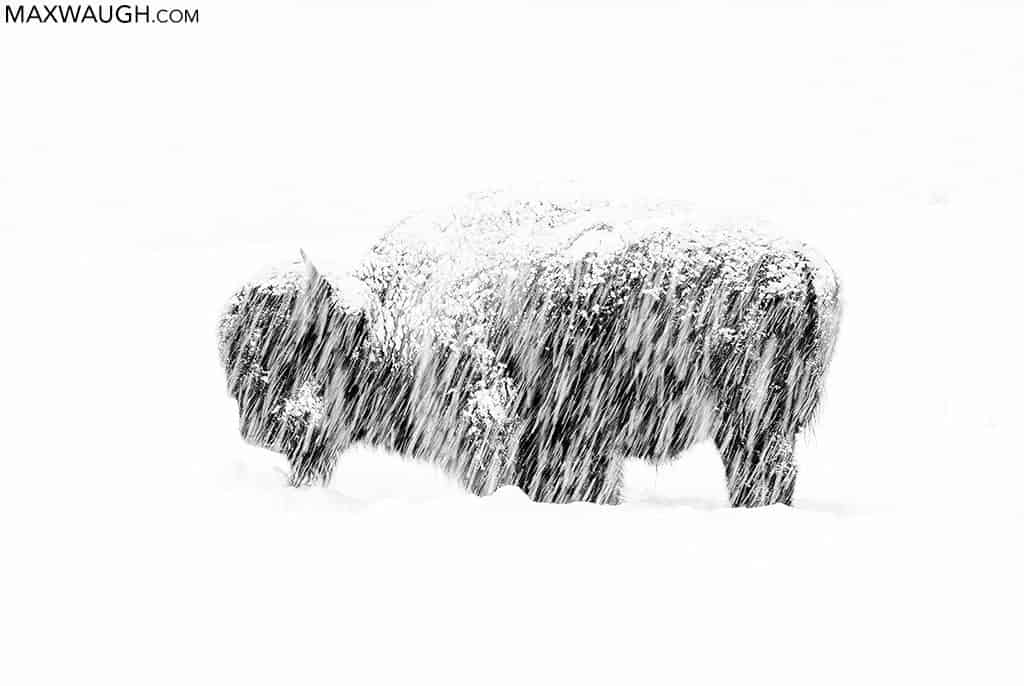

We rounded a bend in the road and I spied a small bachelor herd of bull bison on the slope to my left. They were slowly trudging uphill, stopping occasionally to swipe their heads back and forth in the snow in an attempt to reach buried grass below. The snow fall was thick at this point. The bison appeared as big, vaguely brown silhouettes.

Fortunately, there was a pullout just ahead, where I was safely able to maneuver the vehicle off the road. We quickly rolled windows down and snapped a few shots. One of the bison paused a bit longer than the rest. Soon they had all moved on. We never left the car.

Inspiration, Education, Evolution

When I told this story in various levels of detail to people at the Wildlife Photographer of the Year event last week, it was met with laughs. Mainly because people had assumed I was slaving away in all that miserable, cold weather. Instead of “putting in the hard work” to land a winning image, I was tucked away in the warmth of a large SUV, with nary a snow flake caressing my face. At that point, perhaps, some may have felt I simply got lucky, or that there really was no effort or work that was put into creating the image.

That too would be an incorrect assumption. Because the path that led to the photo actually started several years ago.

Every photographer who was honored in this year’s competition could point to a journey of discovery that led them to create their winning images. Somewhere along the way, they gained insight into the behavior of their subjects, or learned the subtleties of diffusing their macro flash, or perfected the best angle at which to lay their camera trap. We don’t just jump into the field and produce winning photos without learning some hard lessons along the way. The story of the “Snow Exposure” is no different.

The image of a bison in a snow storm, with snow flakes falling in a thick blur, was not the first time I had encountered bison in such circumstances. Nor was it the first time I tried to blur precipitation in a wildlife shot to add texture. Some previous wildlife encounters in Yellowstone helped me visualize what I wanted to do in this scenario and achieve the result I’d hoped for.The idea of trying a motion blur with snow was first planted during a Yellowstone photo shoot with a… duck. In the spring of 2015 I found a Harlequin Duck on the Yellowstone River. The skies opened up and it started hailing soon after I arrived. Instead of just waiting for the storm to pass, I saw a rare opportunity to experiment with hail. So I started “painting” lines through the image with a slow shutter speed, in case any interesting textures could be created across the frame by the falling icy missiles.

The resulting photo did have some nice long lines of blurred hail coming through it, but I didn’t think they were distinct enough against a somewhat busy background. I felt I needed either a cleaner backdrop or even thicker or denser precipitation to make the painting technique really effective.

Less than a year later, in early 2016, I was back in Yellowstone during a winter trip. One morning I experienced a combination of factors that led to a unique photo opportunity. It was a mostly sunny morning, but a quick snowfall formed just as I was shooting a bison with a howling coyote in the background.

In this case, the bison’s telltale silhouette provided the contrasting background for the snow flakes, which were fairly large and glowing thanks to the bit of sunlight that was still shining onto the landscape. It wasn’t until I got the image on the computer at home and converted it to monochrome that they really popped against the dark bison. Though the combination of a howling coyote and bison in the frame was interesting, I particularly loved how the circles of various sizes created a distinct pattern against the bison’s body in the black and white version.

Fast forward two years, to when I had my WPY-winning encounter. The snowfall was thick. I took some shots at faster shutter speeds, thinking at first of my previous winter encounter with the bison and coyote. Could I possibly replicate the circular pattern against these handsome bulls?

In this case the snowfall was too dense… there were too many flakes, and I didn’t have the right backlighting to make the circular pattern show up like it had two years prior. I tried something else. In order to emphasize the bison silhouette as a background canvas I just focused on snowflakes in the foreground, and though I still think the result was interesting I didn’t feel it had the impact I was looking for.

The whole time I had to work pretty quickly, trying these different techniques, since my subjects would soon move on. Then one bull paused…

Knowing that it was impossible to capture any distinct details in the bison’s features behind the curtain of snow, I understood this shoot had to be all about shape, patterns and abstract ideas. I remembered the blurred hail from my duck encounter, and thought it might work with this thick snow, as long as the subject stood still a few moments longer. That’s when I slowed the shutter speed and took the winning photo.

Almost immediately I knew that a monochrome conversion would likely be the best option while processing the image, in order to emphasize the patterns against the bison silhouette (as it had in my 2016 bison/coyote encounter). A high key look helped further accentuate the shape of the animal against a stark background, so it really became all about the bison and lines of falling snow.

I wouldn’t have achieved this shot if I hadn’t gone through the earlier scenarios that allowed me to experiment with different techniques both in the field and during post-processing. While the moment itself was brief, the concept evolved over time and was inspired by my past experiences.

Stepping Back from Your Own Work

I’ve been admitting to a lot of people over the last week—somewhat sheepishly—that I like the photo, but still have mixed feelings about it. Don’t believe me? At the end of 2018, it landed on my “Not Quite Best of the Year” list, just below the picks for my favorite photos of the year.

The problem, if you want to call it that, is that as the artist I look at this image and keep seeing ways that I could try and improve on it. And the more I look at it, the more I’ll keep picking out imperfections. In fact, for years and years I mistakenly thought that WPY judges only pick technically perfect photos… the ones that are tack sharp, are barely cropped and have totally perfect backgrounds. Regardless of whether it was different, or “artistic,” surely there was no way this image was clean enough to qualify. Sure, it was cool… as close to my vision as I’d yet achieved, but I was sure I could do better the next time.

“Exhale. Take a step back.”

That’s what I should have told myself. It’s difficult to gain proper perspective when we’re so intimately involved with our art. Seeing it every day, we are either blindly in love with our creation and glossing over all the (sometimes obvious) shortcomings, or we’re constantly looking for new and different details, uncovering too many perceived blemishes along the way. So we’re usually overrating our own work… or underappreciating it.

In my case, I only began to realize the photo had real potential after posting it online. It struck a chord with my audience, making me think I hadn’t entirely missed the mark after all. People were responding to it much more enthusiastically than I had.

Taking the Shot… and Then Taking a Shot

When compiling a photo contest submission, it’s very easy to just throw stuff at the wall hoping something sticks. One can often submit 15-20 different images spread across different categories in any given photography competition. Wildlife Photographer of the Year is similar. Back when I first started entering WPY, I think I was using the spitball approach. Looking back at my early entries now, I’d probably cringe at the notion that I believed even three-quarters of them had any chance of advancing in a major contest.

These days, I try to take a more measured approach in the rare instances I offer up photos for judging. Enough years of rejection combined with years of experience (which in theory are supposed to make me a slightly better judge of my own work) have led me to be more selective with my entries. When it came to submitting “Snow Exposure,” I had gained enough confidence in it thanks to the initial feedback, to the point where I was certain I was presenting something a little different… even if it wasn’t perfect. Of the dozen images I submitted, it was the outlier, so completely different stylistically than the rest that it stood on its own. It was the only shot to make the next round of judging.

As I mentioned in Monday’s article, the win was still a shock to me. Beyond my own self-criticism, it’s obvious that this isn’t the type of wildlife photo that will appeal to everyone. Anything that is “artistic” or “abstract” won’t connect with an entire audience (one could easily say that about normal documentary-style photos as well, but getting Artsy takes things to extremes). It’s like asking everyone to love Cubism. Impossible. So it was pleasantly surprising that the WPY judging panel got on the same page about it.

And the win didn’t feel cheap. When I finally got to London and had time to examine the other Commended images in the Black and White category, I came away feeling it was one of the strongest categories, top to bottom, in this year’s competition. Though all “confined” to the monochrome world, each photo was so different in terms of style, subject and execution. It was a really great showcase for what’s possible in black and white nature imagery.

Self-doubt, or perhaps a drive to improve upon the photo, still tries to creep in whenever I see it. But the reaction in London went a long way toward reassuring me that the choices I made with this image put me on the right path. It was not universally acclaimed, but in general the reaction was much more positive than I would have expected. That’s gratifying, of course, but more importantly it gives me more confidence moving forward as a photographer. In recent years, I’ve experimented much more with black and white imagery, and I’m constantly fiddling with camera and speed settings to create artistic or abstract images.

When I do this, I’m often unsure of the impending result. It’s all part of the learning process, to see what magic can come directly out of the camera (I’m well aware of the magic of PhotoShop… all of the blur effects above were created in-camera).

I have felt for years that sometimes I’ve gotten too caught up in this experimentation, or perhaps rely on playing around in black and white to “rescue” otherwise dull images. But it’s kept the artistic process fun and has led to a lot of self-discovery. To see a blurred monochrome shot commended by WPY makes me feel even better about occasionally taking my work to the next artistic extreme.

See all of the honored images from WPY55 here.

Read my Behind the Scenes account of the WPY experience here.

If you are interested in ordering prints of “Snow Exposure,” you may order directly through my website or via my Pixels/FAA store.